At Charlie's Cafe With the Beef Trust

A lost tale of plus-sized dancers, skid row and a $400 dinner.

In January 1951, Star Tribune columnist Will Jones decided he wanted to try the $33 dinner for two at Charlie’s Cafe Exceptionale, a Minneapolis institution in its day. He wrote that he had a hard time finding “a dinner companion who would agree to accept half responsibility for $33 of food and drink.” (That’s $415.49 in today’s dollars).

After several prospective dinner companions — and Jones’ own wife — declined the invitation, he finally found someone to binge with. Her name was Violet Morton. Jones wrote plainly, “Miss Morton did not blink an eye at the prospect of eating so much. She is the captain of the Beef Trust chorus line at the Persian Palms. She weighs 320 pounds.”

He stops just shy of saying that this dinner would only be possible if he invited the fattest woman he could think of. Can I just point out that fatness is a weird prerequisite for a dinner invite? Plus, it’s not like there weren’t any hungry men around at the time. Willie Mays played for the Minneapolis Millers in ‘51, and I bet he could’ve plowed through that appetizer plate, too. After all, I doubt he fueled his 16-game hitting streak with cabbage soup. Just sayin’.

Jones noted that the $33 meal wasn’t a prix fixe, just an estimate of what you’d spend if you ordered “the best in the house.” He listed everything they ate, starting with appetizers: “To start, Miss Morton pecked away at a tray loaded with shrimps, smoked oysters, wine-soaked mushrooms, sour-cream herring, cheese-stuffed salami, smoked turkey, eggs with caviar, chopped liver, cottage cheese with chives, assorted pickles, olives and celery.” (Why does the author make it sound like Miss Morton was the only one “pecking” at this heap of appetizers? Wasn’t this supposed to be a dinner for two?)

Next came a Roquefort salad mixed tableside, followed by a two-and-a-half-pound chateaubriand sliced like a roast and “surrounded with Brussels sprouts, tomatoes, cauliflower, and a ring of fancy mashed potatoes.”

Throughout this parade of mid-century noshes, they discussed Miss Morton’s career as a dancer. She told Jones that she and her troupe had recently returned from playing Oklahoma City, where they’d shared an apartment and gained weight on each other’s cooking. Morton revealed that “fat chorus girls lead just about as nice a life as ‘the skinny ones’,” and said that she and her dancers averaged $100 a week in salary ($1,259.05 in 2025 money). They got plenty of attention, too, from men who hung around the Persian Palms.

“We’re always getting proposals,” she told Jones, and added that “the proposals came from thin men.” Morton told Jones she’d been married to a “lanky six-footer” for just under two years and that her weight had nothing to do with their split. He also noted that just because they danced at the Persian Palms, a notorious club on skid row, it did not mean the men they met there were scrubs.

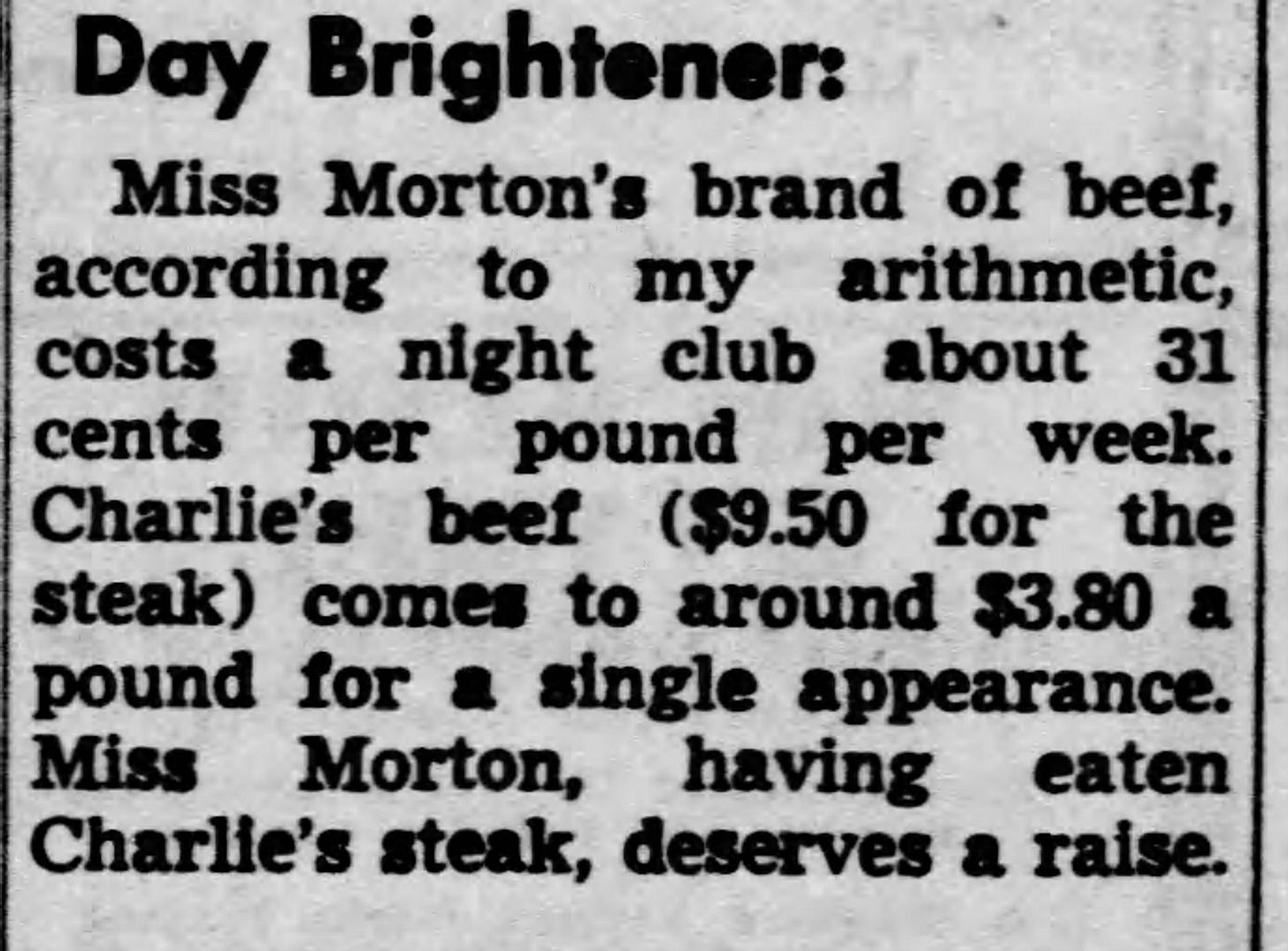

Jones wrapped up his article with this cheeky, if nakedly fatphobic by today’s standards, assessment:

“Miss Morton’s brand of beef, according to my arithmetic, costs a nightclub 31 cents per pound per week. Charlie’s beef ($9.50 for the steak) comes to around $3.80 per pound for a single appearance. Miss Morton, having eaten Charlie’s steak, deserves a raise.”

What was the Beef Trust Chorus?

We don’t know a whole lot about the Beef Trust Chorus as it’s not especially well documented, but the troupe that performed regularly at the Persian Palms in Minneapolis was not the only group to dance under that name.

In a post for Historyapolis, Star Tribune reporter James Eli Shiffer wrote that the Beef Trust Chorus was “somewhat of a fad at the time.” (Follow that link for a better photo of Violet Morton.) I also found an article from about 1960 reporting that women in New York were auditioning to be in a televised Beef Trust Chorus. My best guess is that a Beef Trust Chorus line was similar to a Barbershop Quartet: a trend comprising many different groups doing the same thing but operating independently.

Why the Beef Trust Chorus matters today

A common tactic favored by Instagram trolls is to take random snapshots from the past that happen to show only thin people and point out how much fatter society has become. While it’s true that we’ve gained weight on average since Jones had dinner with Violet Morton, it’s also true that plenty of very fat people existed, and that Lizzo was not the first fat celebrity.

Kate Smith was a popular singer in the 1930s. In 1963, during a Royal Command performance, Paul McCartney made the most historically significant fat joke ever when he introduced the song “Til There Was You” as having been recorded by the Beatles’ “favorite American group: Sophie Tucker.” Oscar winner Hattie McDaniel, who starred alongside Vivien Leigh in Gone With the Wind, was a large woman too.

If Ella Fitzgerald had been recording in the 2000s, when tabloids drew neon circles around the fat on Jessica Simpson’s thighs, would Ella have even had a chance to shatter glass?

When Cass Eliot died, rumors flew that she’d choked on a ham sandwich, because how else could a fat woman die? It was a lie, of course. And by the way, she did not need Autotune.

In my view, attempts to erase fat people from the past amount to little more than a desire to browbeat fat people today. The history of fat celebrities and people like Violet Morton provides an essential counter-narrative challenging the idea that to be fat is to live a miserable life, that to be fat is to not even deserve the right to exist.

The Beef Trust Chorus in fiction

Violet Morton served as the inspiration for Maxine, a character I created for a novel I’m working on. I published the short story version here a while ago. Will Jones’ article provided a wealth of essential information, but it was also the only source I could find, so I used it for the basic structure of my story and built on top of it.

Historical fiction writing tip of the week

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Adventures in Historical Fiction to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.