Backstage at the Persian Palms, Maxine peeled off her sweat-soaked pinafore and dabbed powder between her large thighs. She pasted on a fresh coat of pink lipstick and slipped into her blue fox-fur coat.

“Let’s go girls,” Maxine said to Velma, Lulu, Marcia and Freya -- the girls who made up the Beef Trust Chorus. “They’re keeping the Nankin open just for us.”

“I can’t wait,” said Lulu, “I’m dying for a Singapore Sling.” She spoke with a cigarette clenched between her teeth as she straightened her stockings. Bits of ash fell onto her shoe. She imagined her deep, clawfoot bathtub full to the brim with hot water. She hoped the other girls wouldn’t want to stay out too late. Just because she was the youngest member of the Beef Trust didn’t mean dancing the Can-Can and showing off her substantial rump to drunk, rowdy men wasn’t tiring.

“Lulu, put that out,” Freya said. “It’ll put wrinkles on your face.”

The women slipped out into the night where two cars were waiting and squeezed in. Maxine sat in the front with the driver.

“Hey, Max,” Velma said, “Did you notice? That woman was in the audience.”

Maxine turned around to address Velma in the back seat. “What do I care if she was in the audience?”

Velma grinned. “She came at you with a knife.”

“It was a butter knife. Nobody ever got killed by a butter knife.”

“I don’t know, Max,” Marcia said. “She’s obsessed. She’d do anything to take Teddy from you.”

“I’m not afraid of her.”

At the Nankin, a long dining table was already laid out with all of their favorite dishes: broiled lobster, pressed duck, sweet-and-sour spareribs, eggs Cantonese style and heaps of fried rice with crabmeat. Red paper lanterns hung from the ceiling. Two small turtles dozed in a glass tank.

They checked the furs and hats and sat down as a waiter rushed around to take their drink orders. Maxine took a lobster tail and broke the shell with her hands. To be in the Beef Trust Chorus, a girl had to weigh at least two hundred pounds. They danced the cancan in short dresses that showed off their satin underwear and made one hundred dollars per week doing it. Typists and stenographers were lucky to make seventy dollars a week.

Reducing just wouldn’t do.

“So nice of Walt to keep the place open and have our standing order ready. “I never get tired of these,” Marcia said, nibbling on a sticky spare rib.

Lulu hummed along to the first few bars of “Stranger in Paradise,” which was playing on a jukebox. Then she made a face and began pawing through her coin purse in search of a nickel. “This song could knock out an elephant,” she complained. Her chair skidded backward as she got up. “I’m going to put on some Fats Domino or Chuck Berry.”

Velma picked up a chopstick and stabbed the air and laughed. “I am the one he loves!” Velma trilled.

“She never actually said that,” Maxine said. She took the lime from the rim of her Cuba Libre and bit down.

“Didn’t she?” Velma asked.

“No, she didn’t,” Freya said. “She screamed something, but it wasn’t that.”

“Well, if you don’t know what she said, how can you say that’s not what she said?”

Freya pulled a cherry stem out of her mouth. It was knotted in the center. “Because she was speaking in tongues or something. It didn’t make any sense.”

“It sounded like caveman grunting to me,” Lulu said.

Velma glanced at the other girls before picking up the knife again and shouting, “Ooga booga!”

The laughter of the other four drowned out the music from the jukebox and echoed through the empty restaurant.

After they paid the check, Max waited under Nankin’s fake pagoda awning while she waited for a cab. She pulled her coat tighter around her as a cold breeze swept through the street and watched as the neon sign that said Nankin Cafe went dark.

When a cab finally pulled up to the curb, she climbed into the back seat and sank down into the leather. As the cab sped away from downtown and over the bridge, the bright, pulsing lights gave way to dark, slumbering streets where the only light was from streetlamps and the occasional still-glowing window.

Max tipped the driver and rummaged for her house keys. The street lamps cast a wan light over the half-timbered facade and the jack pine that stood guard near the front door gave off a sharp scent. Light filtered through the branches, and Max noticed light coming through a window in the house next door. The neighbor’s small dog barked. Max hoped it was the husband who was awake and not the wife; she didn’t need that church mouse eyeing her over the back fence, coyly twittering like a tiny bird, saying something like, “You got in awfully late last night. What on Earth could have kept you out so late?”

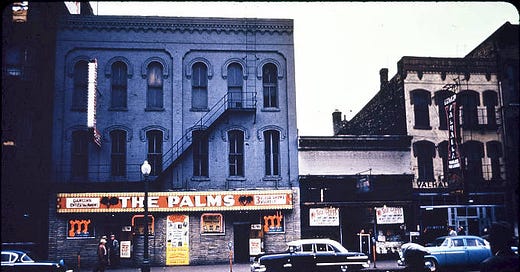

The Persian Palms was in a part of town that respectable people just didn’t visit unless they were from out of town, like the small-town mayor who ran up such a tab he had to cover it with a check. (The bartender crumpled it up, claiming the signature was illegible, and demanded a new one. Then Harry ironed the first check and cashed them both.)

If she knew Max worked at the Persian Palms, she’d rally the neighbors to drive her and Teddy out of their house.

The husband knew. Max had seen him there a few times, huddled in a corner with a group of other men. From the stage, Max locked eyes with him and he seemed to freeze as he gripped the neck of a sweating beer bottle. Max gave him a slight nod, and he nodded too, and that was that -- she wouldn’t tell if he wouldn’t.

Once inside, Max locked the door behind her and shed her coat. It wasn’t a large house, but the living room had enough space for Teddy’s baby grand piano and picture window that looked out on the park across the street. Three small steps led to a landing where you could turn and go up a long staircase to the second floor, or go straight and take three steps down into the kitchen. It was a peculiar setup; it was months before Max could get in and out of the kitchen without tripping.

She put her leftover Chinese in their brand-new Philco refrigerator and went upstairs. How the woman next door had gawked when the delivery men brought the new fridge through the alley! She’d stood in her yard, hanging sheets on the line, with how-do-they-rate stamped all over her slackjawed puss as her dog ran back and forth along the fence.

Max didn’t understand why the neighbors should be so jealous; they were the ones with a turntable in their garage so the husband never had to back his gleaming black Studebaker into the street.

Max slid into bed where she wrapped an arm around Teddy’s waist, her fingers stroking his muscular chest. He stirred and turned to face her. The light from the streetlamp shone on his hair; it was silver and black, like a chinchilla stole.

“Did you bring me a doggy bag?” he asked, groggily.

“Spareribs and crab fried rice.”

“Give me a taste,” he said as he kissed her. “How was the show?”

“Same as always,” she replied. She stroked the stubble on his cheek. His blue eyes twinkled, even in the dark. “Your old flame was there.”

“What old flame?” His hand rested on her hip. She laced her fingers through his.

“Don’t you remember the butter knife incident?”

Teddy sat up on his elbow. “You mean Rita?”

“Velma saw her. I didn’t.”

“She was there? At the Palms? Gee, Max, I don’t think I like the sound of that.” His hand slid from her hip to the small of her back.

Maxine sighed. “Why is everyone so worried? I’m not afraid of her.” Since joining the Beef Trust Chorus two years ago, she was in the best shape of her life. She was the Rocky Marciano of Skid Row burlesque. Why should she be afraid of that featherweight?

Teddy sat up and switched on the lamp. “That woman should be locked up.”

Maxine stroked his fingertips with her own, thinking of the way his fingers danced across the piano keys, eager for them to do the same to her.

Maxine squeezed Teddy’s hand. “So call the men in the white coats.”

He kissed her and drew her in closer. He switched the light off again as they both sank under the covers.

“She is pretty,” Maxine said. “She probably thinks she’d look better on your arm than I do.”

“I don’t think she’s all that pretty. Not with those eyes. She looks like they hypnotized her in the asylum and then dumped her off down by the river. Besides, She’s like all the other small-waisted girls from the steno pool. Simpering over their typewriters and dying for an engagement ring. They don’t have your heap of wheat.”

He stroked the warm skin between her supple rolls of flesh.

“I love it when you recite the Song of Solomon to me,” she muttered drowsily.

He lowered his voice and whispered, “Thy belly is like a heap of wheat beset by lillies, thy breasts like the twin fawns of a gazelle…”

He kissed her as she drifted off to sleep.

During the day, the Persian Palms was the kind of place where a man could meet a woman who’d take him to one of the rooms above it and show him a good time for an hour -- two, if he could afford it. By evening, the whores cleared out and the dancers took over. The Persian Palms boasted three floor shows every night, featuring strippers mostly, as well as comedians, female impersonators, Divena the Aqua-tease, and the Beef Trust Chorus. Some of the strippers worked overtime as B-girls between shows, leaning over the bar with their short skirts hiked up, their asses out there for anyone to grab.

Last summer, on a night in August when the mercury had refused to drop below ninety for four days straight, two men brawled on the street in front of the Palms. One stabbed the other who staggered into the Persian Palms, collapsed on the grimy runner, and died. That was when Jeannetta, who’d been the captain of the Beef Trust Chorus, decided her dancing days were done, and Maxine took over as leader of the troupe.

Still, there were worse places than the Persian Palms. It may have been surrounded by flophouses and the down-and-out men who paid a few cents a night to sleep in chicken wire cages, but the Palms was off limits to the likes of them. Harry was not the kind of guy who’d sell five cents worth of muscatel to bums at eight o’clock in the morning to save them from the DTs. The Palms was where you went if you had a big bankroll and didn’t care if you were busted out at the end of the night.

Max did her best to avoid the area when she wasn’t working. Walk down the streets, and maybe you’d hear music coming from a jukebox pouring through a bar’s open door, or the laughter of men lounging in the park, or voices singing hymns in one of the gospel missions, or a baseball game on a radio coming from the window of the dayroom at a flophouse. You could buy some nice jewelry at a pawn shop, or some outdated clothes for cheap, or maybe coffee and a day-old pastry for next to nothing. But you’d also see somebody slumped against a wall in the middle of the day, groups of men passing around bottles of wine, alleys full of “dead soldiers” and shattered glass.

The flophouses didn’t let women in, but the smell followed the men wherever they went: old sweat, backed-up toilets, baked beans, beef stew, cheap tobacco, cheap beer. Max was glad they stuck to the dingy little places like the Sourdough Bar and the Valhalla where they could drink all day long and spit on the tile floors. Max rarely ventured beyond the Persian Palms, unless Teddy was performing at Jimmy Hegg’s on Second Avenue on the same night. Then, she’d sneak over between floor shows without bothering to change out of her costume. Some of the bums would hoot and holler but they didn’t judge.

In the morning, Max drove Teddy to the airport. He had a meeting with his music publisher in New York City. When she returned home, she brewed a pot of coffee and sat on Teddy’s piano bench, looking out at the park across the street. The row of pear trees that shaded the bus stop dropped delicate white petals into the bright new grass. Max closed the piano lid so she could recline without hitting the keys and watched children climbing on a geodesic jungle gym. Come July, the metal rungs would be too hot to touch.

As she sipped her coffee, she noticed a turquoise Chevy Bel Air driving very slowly past the park, obscuring her view of the jungle gym before rolling through the intersection and vanishing. That’s when Max noticed fingerprints on the window. She went to the kitchen for Windex and a page of old newsprint. She spritzed the window with the blue liquid and wiped it away, but the greasy fingerprints were still there.

They were on the outside.

Max crumpled the wet newspaper in a tight fist.

In the afternoon, she walked down the street to the butcher shop and then back up through the park to the little grocery store across the street. The children were gone and the park was empty save for a pair of squirrels chasing each other around the trunk of an ancient oak tree. She bought potatoes to go with the Swede sausage she’d make for Teddy when he came home from New York, some Creamette macaroni noodles, and a can of tomatoes for the dinner she’d eat alone tonight.

The stoplight was green when she reached the other end of the park. As Maxine stepped off the curb, the turquoise Bel Air she’d seen earlier barreled toward her, its engine rumbling. She jumped back and tripped backward over the curb, landing on her tailbone. The car whipped around the corner, and Maxine couldn’t see the driver’s face, just a cloud of black hair.

Her heart pounded and her limbs trembled. She picked herself off the curb. Her paper shopping bags had torn, but at least the butcher paper around the Swede sausage was still clean. Max hurried home and dialed Velma’s phone number.

“Velma, did you notice if Rita had a bouffant?”

“Who’s Rita?”

“Rita! The butter knife! You said you saw her at the Palms on Saturday night.”

“Oh,” Velma coughed. Max heard the slosh of Velma’s martini shaker. “Yeah. She had a bouffant. Big as life.”

Maxine’s hand shook as she hung up the phone. She poured herself a glass of Beefeater gin. She called the police and then Teddy’s hotel (Pennsylvania 6-5000) and left a message with the girl at the front desk.

The police came to her door but said there wasn’t much they could do without a license plate number -- there were hundreds of turquoise Bel Airs driving around.

“Can you describe the driver?” the younger of the two officers asked. He scribbled on a small notepad.

“She has black hair in a bouffant. And she’s skinny. She’s pretty in a prom-queen sort of way.”

“What the heck is a bouffant?” the older officer asked.

“You know, all puffed up. Big,” said the younger one. He held his hand high above his head as if he were measuring a pile of imaginary hair.

“Anyone see this happen?” the older officer asked. “What about your neighbors in the house next door? They’re right on the corner. Could they have seen it?”

Good God, I hope not, Max thought. “I dunno,” she said, softly. “Maybe.”

“Well, listen,” said the older cop, “Any time this woman pops up, you write it down, got it? Keep a log. We’ll do what we can but you gotta do your part, and that’s keep a note of everything she does.”

“Sure,” Max said.

She left the Creamette noodles and the can of tomatoes on the kitchen counter and went to bed early. By the time Teddy called back, she was already asleep.

“Are the bruises that bad? Do you think they’ll show? Maybe I should have Marcia take my part tonight.” Maxine stood with her back to a mirror, looking over her shoulder at the bruises on her thighs.

“That’s not the reason you shouldn’t dance tonight,” Teddy said.

“I called the Palms. They have Rita’s description. They’re not going to let her in.”

She sat next to him on the bed. He slid his fingers into the hair at the nape of her neck.

“Wouldn’t it be better to get away?” he asked. “We could go to Hawaii. We could pick coconuts and go to a luau.” He tugged on the strap of her satin slip and kissed her shoulder. His other hand rested on her belly, his fingers splayed. Teddy liked to compare her body to sweet roll dough; when he touched her, he remembered the feeling of warm dough rising under a cloth in the kitchen of his childhood home.

“I could learn to hula. I’ve heard it’s a style of dance that favors fat women. It could be good for the act…” Maxine sighed. She stood up and put her hands out in front of her, making waves with her fingers as she shook her hips from side to side. Teddy grinned.

“So, let’s go,” he said. “I’ll join a ukulele band.”

She gazed deeply into his blue eyes and noted that they were almost the same color as the car that almost hit her.

“She’s not going to run us out of town, Teddy,” Maxine said.

Through a gap in the curtain backstage, Maxine scanned the crowd for signs of Rita but there were none. The bouncer had been true to his word and kept her out. But that didn’t mean she wouldn’t show up someplace else.

Curls of smoke rose from crystal ashtrays at every table. Sawdust covered the floor. The businessmen sitting at tables had B-girls draped over their arms, wobbly from splits of champagne. Maxine was fascinated by the B-girl grift, conning men into buying overpriced champagne that was barely a step above ginger ale and taking a kickback from the bartender for every sale.

Maxine stood up straight as Velma tightly knotted her pinafore behind her back.

“You don’t see her?” Velma asked. Maxine shook her head.

When the music started, the dancers raised their ruffled skirts and showed off their underwear to a crowd of men who clapped and whistled. Maxine and Lulu held one ankle above their heads and pirouetted on the other foot while the other girls lay flat on the stage and kicked at the air. Sweat ran down Maxine’s back. Her rear end felt sore from where she’d fallen on the pavement. Marcia turned a cartwheel. Velma did a split jump. They finished the number in formation, all in a straight line, high-kicking in perfect unison.

Still no sign of Rita.

The rest of the night was the same as always: thirty-minute break, second show, thirty-minute break, third show, midnight spareribs at Nankin.

When she got home, she crawled into bed with Teddy, but she couldn’t sleep. Every time a car’s headlights sliced through their curtains, she snapped to attention. At three o’clock, she heard a familiar rumbling sound and followed it downstairs to the sunroom. Two bright beams of light burned through the windows. Maxine winced and shied away from the light, but her eyes adjusted just enough to make out the silhouette of hair piled high. Maxine’s body tensed. She waited for the car to drive away but it just sat there with its headlights burning through the daisy pattern on the lace curtains. The hairs on the nape of her neck stood on end. She slipped her silk kimono around her shoulders but still felt cold.

Maxine remembered meeting Rita for the first time. Between shows at the Persian Palms, Rita appeared in the dressing room. No one could remember why she was there or who had invited her. Later that night, Maxine stood backstage with Teddy when she saw Rita hanging around the dressing room door. Max locked eyes with Rita, who disappeared into the shadows. As Max and Teddy walked toward the exit, she caught sight of an eye staring at her from a narrow gap between two stacks of empty wooden beer crates.

A week later, Rita followed the girls to Nankin after the show and charged at Maxine with a butter knife. Maxine was still sore from her fall when Rita’s car nearly hit her, and now she was sitting out there flooding Max’s bedroom with retina-searing light, a spotlight for a floor show that Max wanted no part of.

She reached for her diary, glanced at the clock, and wrote a new entry:

April 20th, 1957

3:08 a.m.

Car in the neighbor’s driveway across the alley shining headlights into our windows. License plate: 657HGF.

She closed the notebook and held it against her chest. When she looked out the window again, the car was gone.

Upstairs, she woke Teddy. “Hawaii,” she said. “Let’s go.”

Teddy called an Army buddy who booked a discounted room at the Royal Hawaiian and a residency at a Honolulu jazz club called the Zebra Room. Max called a meeting of the Beef Trust Chorus and told them that Lulu would be captain while she and Teddy were away.

They boarded a Northwest Orient Airlines flight bound for Seattle, where they changed planes and took their seats on a Stratocruiser that would take them to Honolulu. Teddy and Maxine slipped out of their seats and down the narrow, spiral staircase that led to the lounge. Max tensed at first -- the staircase looked awfully narrow, and she didn’t want to set that co-pilot up for another joke. But while it was a little tight, she made it down to the Fujiyama Room without anybody making a smart-alecky comment about buttering her up.

The Fujiyama Room was a lounge with a horseshoe banquette, a fully stocked bar, and little bonsai trees in the corners. They took a seat at one end of the banquette and ordered Cuba Libres from the bartender. In the center of the horseshoe, a woman in a silk jacket and pencil skirt held up a cigarette while a man in a grey suit lit it for her.

“She’s in Dior,” Maxine whispered to Teddy. “We’re really hobnobbing with the movers and shakers now! I can hardly believe we can afford this.”

“Well, that $100 a week you bring in from dancing sure helps,” he said. “We’ll pay this off in no time at all.” When he’d called to book the flight, the woman on the other end of the line told him about Northwest Orient Airline’s “Fly Now, Pay Later” program -- all he had to do was put down ten percent, and he could pay it off over twenty months.

Darkness had fallen by the time they reached their hotel. Max stood on the balcony, hoping to watch the waves toss moonlight, but gauzy clouds hid the moon and stars. She collapsed into bed next to Teddy, the balcony door still open, the sounds of the waves hitting the sand drowning out her dreams.

They slept late. In the afternoon, Teddy went to the Zebra Room to rehearse with his new drummer and bass player. Max went down to the beach and floated in the warm water, looking up at the sky. It was clear now, a hard jewel-toned blue.

Later, wrapped in a damp, sand-spangled towel, she walked across the beach to a grass-roofed hut and ordered a drink. Next to her, a girl in a yellow dress stared down at her feet, her face streaked black with mascara. Max looked at the girl, then traded glances with the bartender who shrugged and poured grenadine over ice.

“What’s the matter? Is there something we can do?” Max asked the girl.

“He was supposed to meet me here, but he never came,” the girl said. She began to cry again, as if saying it out loud was a ripped-away scab.

“I’m sorry,” Max said. “Some of them are no good.”

“I even dyed my hair,” she said, tugging on a bleached strand, “and cut it to look like Marilyn Monroe.”

“It’s not your hair,” Max said. “You could look like Marilyn in every way and this could still have happened. No woman gets everything she wants. Not even Marilyn.”

“Oh, what do you know?” The girl snarled. “Look at you.”

The girl turned and walked away, her arms crossed, kicking up sand.

“Poor kid,” Max said to the bartender.

“Yeah she must be,” he said. “She didn’t tip.”

That night, Max sat alone at a table at the Zebra Room. A bas-relief mural stretched across the wall, showing carvings of plants and elephants and warriors holding spears aloft. On stage, Teddy and his band played “September in the Rain.”

She glanced at the empty chair at her table and thought of the girls back home, of their late-night dinners at Nankin, of the hours they spent rehearsing new moves, of all the laughs they had. Couldn’t they bring the act to Honolulu?

Max sighed, knowing she and Teddy would leave Hawaii once his residency at this club was done. Hawaii would recede into memory as soon as they got on a plane bound for home, and in Minneapolis, she’d find everything as she left it.

Well, not everything, she hoped.

Author’s note: I am currently working on a version of this that will be a novel. The Persian Palms really did feature an act called the Beef Trust Chorus. Read about it here: http://historyapolis.com/blog/2016/07/21/the-persian-palms/