The Terror of Sweet Briar

One block off the main drag, on a street that dead-ends at the freeway, you discover a building from another time. Most of the garden-level windows are boarded and you can tell it has been a while since anyone lived inside. You know trespassing is a bad idea. You could get arrested. You could fall through a rotted staircase or be stabbed by a squatter or break your skin on a dirty needle. But still, there’s no harm in getting a better look. Is there?

The Sweet Briar Flats are four stories high, made of red sandstone, and built in a Romanesque style that favors large, rounded archways. An iron fire escape spirals skyward. It decorates the red-brick building like a twist of Christmas ribbon. The windows are massive. In a bygone era, someone wealthy lived here.

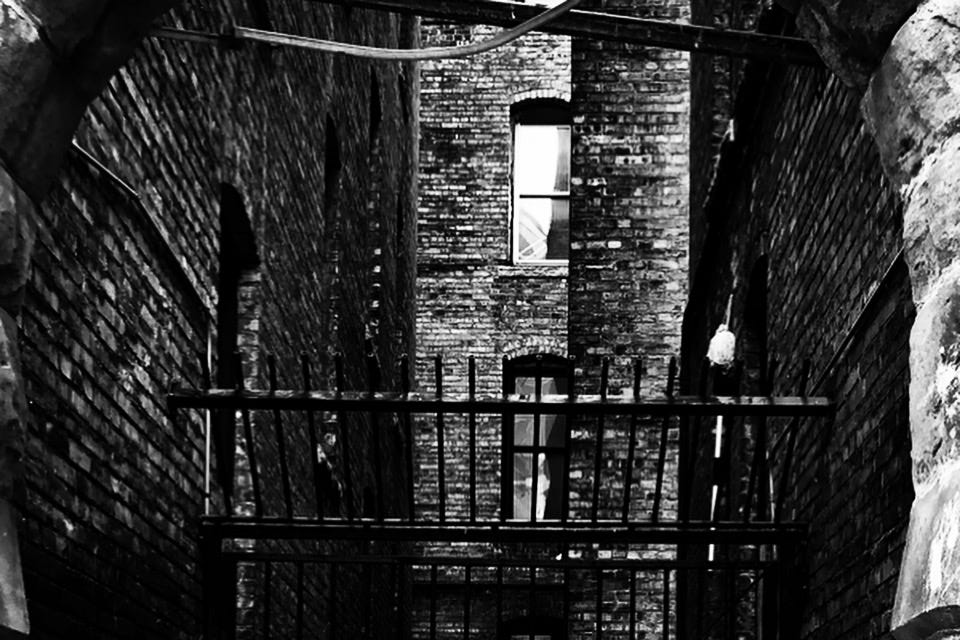

You take half a step into the red-stone archway that leads to a wrought-iron gate and a maze of rear-facing windows. The smell hits you right away: rot. Wet wood. The smell says: stay the fuck out of here. The air in the archway is cool, several degrees cooler than the pavement on the other side. You imagine that this might have been a nice place to escape the heat on a scorching summer day. But now…How can those windows be blank and still have so many eyes?

You’ve heard tales of narrow hallways, of caved-in ceilings, of doors nailed shut following police raids. You’ve heard complaints of black mold, used needles, and straws cut up for heroin smoke. Before the last tenants were forced out, they said there were mice, cockroaches and bedbugs. In spite of all of that, the last tenants of Sweet Briar wanted to stay. It was better than nowhere. It was home.

May, 2010

Notice to Vacate

Dara couldn’t sleep. Her scalp ached and no matter which way she rested her head, she could feel that sharp tugging. Why did Titi always have to do her braids so tight? She heard someone staggering in the hallway and snuggled close to her dad. Still asleep, he wound a muscular arm around her, hugging her small shoulders.

In the morning, she would watch out for needles in the hallway as she left for school. Dad said she could get sick if she stepped on one, but she mainly worried about how much it would hurt. Dad would wake her up early so they could make pancakes. He sometimes let her pour the batter onto the griddle. She liked to watch the bubbles form and pop. Then, she would tie her sparkly pink sneakers and zip up her Princess Tiana backpack, the previous night’s homework ready to hand in. Dad would drive her to school.

Dara didn’t want to go to the homeless shelter. They wouldn’t be able to make pancakes there. Someone might take her backpack or sneakers. Dad promised they wouldn’t go to the shelter and Dara wanted to believe him, but he was still looking for a new place. He said that the building had been sold and that the new owners wanted to fix it up, but first everyone had to leave.

Dara didn’t understand. Couldn’t they stay and help make it nice? Dad shook his head and said it didn’t work that way. It would be too expensive after the work was finished. They had to leave so that people with more money could move in. But if those people had more money, Dara asked, couldn’t they just go someplace else? Dad just nodded and looked away.

The apartment had some things left in it from when it was nice a hundred years ago, like the fireplace with the pretty blue tiles all around it and the big mirror on top. They couldn’t light real fires in it, but Dara had pretend fires, and liked to imagine that she was cooking a magic potion in a big cauldron.

Hours later, after breakfast, Dara was tying her shoes when someone knocked on the door. Dad answered. Dara heard a man ask, “When are you moving?” The man sounded angry. Dara made her meanest face and hoped the man would be scared of her. She decided that one day, she would be a bajillionaire so she could buy his house and make him move to a shelter.

The man left and Dad turned around and noticed Dara’s scary face. He laughed softly and folded his large hand around her small one.

The rear of the building is guarded by razor wire and two chain link fences. In the yard, an old wooden door splits and peels and melts into the dead grass. All the windows back here are boarded. The yard seems much too small for such a large building.

There’s no way in -- not here, anyway. On the other side, there’s a narrow gap where the chain link has been shredded and pulled back. Bits of chain link on the ground suggest that the fence was cut recently; the metal looks new. There’s a way in, but if you go you won’t be alone. You know you don’t want to meet the person who wasn’t afraid to go inside.

August, 1982

Call for Service

The officer turned off the siren but left the lights on as he parked outside of the Sweet Briar Flats. He hated responding to calls here. What was the point in canvassing the neighbors if they never wanted to talk? Most of the tenants were involved in some kind of illegal shit. They wouldn’t snitch unless offered a plea deal.

The front door was open, so he stepped inside. The place reeked of cigarette smoke, vomit and cat piss. The hallways were narrow and some of the cheap wall sconces were burnt out. Sweet Briar was beautiful on the outside. It was a shame that the owners refused to take care of it, but what could you expect from landlords who took deposits from people and then didn’t let them move in?

The officer found the victim in one of the communal bathrooms, in the tub, face up with a knife protruding from his chest and a blood stain on his shirt. His eyes and mouth were wide open. A neighbor lurked in the doorway.

“I need the bathroom,” the neighbor said.

“Did you see anything?” the officer asked. The man shook his head. “Hear anything?”

“I heard him yellin’ last night,” the neighbor replied. “But I didn’t think nothing of it. There’s always yellin’ around here.”

“What was he yelling about?”

The man just shrugged. “Can I use the bathroom now?” he asked.

“This is a crime scene,” the officer said incredulously.

“There’s only two bathrooms on this floor and someone’s in the other one.”

The officer shook his head. Ninety-six apartments and only thirty-eight bathrooms between them. The suits down at city hall had to be out of their minds. Why didn’t they revoke that slumlord’s license?

Meanwhile, nobody in this roach-hole would ever talk. Nobody in town ever talked. The police chief was out of his mind if he thought the clearance rate was ever going to go up.

It’s a little bit funny that there is still a satellite dish on the roof. Do signals from space still bounce off of it even though the building has been empty for three years? You didn’t notice the dish until you stood across the street. From there, you can see into the first-floor windows, which are high enough from the street that they don’t need to be boarded up. The apartment has white walls and a door that’s broken. A six-inch-wide section of the wooden door is gone like someone kicked it in. Behind it: a dark hole.

July, 1968

Daisy Girl

Under the archway, the red sandstone bricks provided a cool refuge from the summer heat. Melody stood with her back to the windows that glowed with lamps and TV screens and lit a cigarette.

“Mel,” a familiar voice said. She looked up and saw Derek standing in front of her. His shaggy blonde hair was greasy and his jeans were flared at the bottom. “What are you doing down here?”

Derek lived in one of the apartments that faced the air shaft.

“Getting away from the fumes,” Mel said as she passed him her cigarette. “My mother is on one of her cleaning jags. Once a month she loses it and scrubs and polishes everything in the apartment. Between the oven cleaner and the silver polish and the Hi-Lex it’s like an H-bomb went off in there.”

Derek exhaled a stream of smoke and handed the cigarette back to Melody.

“She doesn’t make you help?” he asked.

“She doesn’t want help,” Melody replied. “It’s a private ritual for her. An exorcism.”

“Exorcism of what?” Derek asked.

Melody took another drag and crushed the cigarette with the toe of her sneaker. She shook her head. “Beats the hell out of me. My dad’s ghost? Hitler? The Big Bopper? Could be anybody.”

“Say, do you still work at the Hollywood?” Derek asked.

Mel shook her head. “My mom made me quit when they started showing pornos. Why?”

Derek shrugged. “I’m bored. I thought maybe you could sneak me in.”

An awkward silence passed between them. A window opened, releasing the strains of a Bing Crosby tune playing on a crackling radio. Derek grimaced.

“Now that apartment needs an exorcism,” he muttered.

Mel grinned. “That gives me an idea. One time, there was a bat in the apartment, and my mother blew up like Daisy Girl. If we could get one and let it loose in the apartment, she will scream louder than an air raid siren.”

Derek ran a hand through his greasy hair. “I know how to catch bats,” he said.

They hopped into Derek’s car and drove down to the river. The rushing water made a loud sound as they scooped bats out of the red sky with fishing nets. The bats hissed as Derek shook them into a cardboard box that Melody held open. Melody closed the box and could feel the bats’ wings beating against the sides.

“Let’s get home quick before they get out and tear us apart!” Melody said as they raced to the car.

Once they returned to the apartment, they crept up a spiral fire escape until they reached the fourth-floor window that opened to Mel’s mother’s bedroom. Quietly, Melody eased the window up while Derek gingerly opened the box. They heard the beating of bat wings and slammed the window shut, flattening themselves against the wall so they wouldn’t be seen. They gripped each other’s hands and laughed without sound. Seconds later, a full-throated scream filled up the night.

One of the first-floor windows has a parabolic crack that runs from one side to the other, like a frown. Behind the dirty glass, you can see a radiator that’s covered in gold paint. On the wall, black slashes of permanent marker form the words YOU LIE ALL THE TIME.

February, 1937

Cephalophore

“Devil cat,” Clara thought as she passed her neighbor Suzy’s window and saw the cat sunning itself on the sill, its jet-black fur glittering in the light. How could Suzy bring that animal into the building? He brought messages from Satan. Clara heard them when he mewled on the other side of the wall. It was a thin wall they put up when they divided the apartments. Thirty years ago, it had been one apartment. Back then it was a nice place to live. Now it was a bargain and full of witches like Suzy and their demonic cats.

Clara had complained to the landlord, but he wouldn’t do anything. All he would say is “Cats are allowed.” Plus, Suzy kept the place nice and she paid rent on time. He wasn’t going to ask her to part with her pet.

Realizing that she would have to take matters into her own hands, Clara shoved her bed away from the wall and took a paring knife from the kitchen drawer. With the tip of the knife, she etched a cross into the white paint and wove a climbing rose around it. When the symbol didn’t stop the cat’s cries, Clara went to visit her priest at the cathedral and asked him to come and bless it.

He put his hand on her shoulder and told her that a cat was just a cat. Perhaps there was something else troubling her?

Clara shook her head. Why didn’t he understand? If there was anyone who should be concerned about Lucifer’s emissaries…

Behind the priest, sunlight burned through the stained glass and stretched the blue robes of Saint Denis across the hardwood floor. Clara looked up at the beheaded saint, clutching his own head in his hands. “Nothing terrifies the devil more than lips that don’t open,” she thought.

Back at the Sweet Briar Flats, Clara waited. She knew what time Suzy came home each day. The cat would be waiting by the apartment door. (Only a cat possessed by demons would do something so contrary to its own nature.) Clara put a piece of raw fish on a plate and waited, watching through the tiny peephole.

At quarter after five, Suzy appeared in the peephole’s lens. Clara opened her door and set the fish on the floor in the hall. Suzy unlocked her door and the cat darted out. As it nibbled the fish, Clara grabbed it by the scruff and slammed the door.

Suzy called the cat’s name. Midnight? Midnight? She knocked on Clara’s door. Clara ignored the knocking. The paring knife, still flecked with white paint, was on the floor next to the charm she’d made. The cat squirmed and hissed as she brought the knife close to its neck. With its paw, it swiped at her arm and left a long scratch that started to bleed.

Clara heard the doorknob turn.

“What the hell are you doing?” Suzy shouted. She reached for Clara’s phone and asked the operator to connect her with the police. The cat hissed and batted at air with his paws as if he were trying to run.

Without thinking, Clara opened the window and threw the cat out. A gust of cold wind hit Clara in the face as she looked down on the animal, motionless on the pavement save for a flick of his tail. When the policeman arrived, she told him the cat jumped of his own accord.

“She’s lying,” Clara overheard Suzy tell the cop. “She lies all the time.”

Under the archway that leads to the iron gate in front of the maze of windows, you notice things that weren’t there before. In front of the gate, there is a pair of spiral-bound notebooks like the kind high school kids use, the handwriting on the pages ruined by rain. Next to the notebooks: a used condom. There’s a pile of sweatshirts on the ground.

Beyond the iron gate, a white, graffiti-covered door is open. The squares of plywood that were meant to hold it shut have failed. That door wasn’t open before. There is someone inside. There’s someone inside right now. You notice that the door has holes in the top of it. Are they from bullets? Cold, moldy air winds around you like toxic vines. A shiver rattles your spine.

What malevolent spirit lives here? Haunting each of the ninety-six apartments in its turn? Breaking doors and writing YOU LIE ALL THE TIME on the wall? Throwing open the doors to empty cabinets to search for abandoned sacks of sugar or forgotten knives? Who shatters windows and etches the word “exploit” into the red sandstone? Who sleeps here, letting that mold stench soak into their clothes?

October, 1900

Floriography

Ireland never felt so far away. Nora knew she should be grateful for Father Reid for helping her get this job, but as she glanced up at the red-brick building, she felt a tug of homesickness. Nora stepped out of the carriage and rubbed the gray Percheron’s crest while the driver unloaded her small steamer trunk. Above the entrance, golden letters spelled out the name of the building on a glass transom: Sweet Briar Flats.

Sweet Briar? In the language of flowers, sweet briar meant “wounded.” A bouquet of briar roses meant your beau was in an infirmary somewhere.

A young man came out to help the driver with Nora’s trunk. She followed them into the building. Inside, gas flames flickered inside cranberry glass sconces, making the corridors glow like the inside of a ruby. A gas lamp affixed to the staircase’s newel post was in the shape of a woman, cast in bronze.

With each step, Nora noticed the scent of a different flower. Roses: love and passion. Irises: royalty and wisdom. Amaryllis: success and pride.

A matronly woman not much older than Nora herself answered the apartment door. She wore her hair in a beaded snood and a dress made out of brown silk. Everything in the apartment gleamed: the ornate fretwork made from cherrywood, the oak floors, the brass chandelier with its white, tulip-shaped hobnail shades. A glare of sunlight reflected off of the black-lacquered surface of the grand Steinway in the parlor. The cobalt-blue tiles around the fireplace shimmered. The brass wall sconces were adorned with little winged cherubs.

On a table, a crystal vase held a bouquet of orange lilies: hubris and disdain. Nora cringed and then immediately changed her expression so that Mrs. Ellis wouldn’t notice. Mrs. Ellis led Nora to a small room at the far end of the flat. The room had only one plain gas sconce on the wall and was only slightly larger than her room back in Dublin, but the window was tall and let in a lot of light.

“Rest up after your journey,” Mrs. Ellis said. “You can start work in the morning.”

Nora’s life with Mr. and Mrs. Ellis did not vary much from day to day. First thing in the morning, she woke up and lit a fire in the parlor. She cooked breakfast and helped Mrs. Ellis get dressed. She gathered the linens and clothing to take to the laundress and served drinks to guests. She made lunches and dinners in between hours of sweeping, scrubbing, folding and sewing. After the couple went to bed, she tended the fire until it went out and made sure all of the gas burners were turned off.

On one unseasonably hot afternoon -- Mrs. Ellis called it Indian Summer but didn’t explain why -- Nora noticed the janitress on the staircase, struggling with a scrubbing pail. Nora grasped one side of the handle and together they carried it to the landing.

“Thank you,” the janitress said. Her wrinkled face was red and sweaty. “I’m getting too old for this work,” she said, between gasps for breath. She looked Nora over and asked, “You work for that Ellis woman?”

Nora nodded.

The janitress lowered her voice. “You be careful, now. That one goes through girls faster’n anybody I ever seen. She’s runned three girls off already.”

Nora’s stomach tightened, pushing bile into her throat. She swallowed hard, and remembered the look Mrs. Ellis had given her earlier that day. Nora had been washing the dishes, and Mrs. Ellis came into the kitchen and glared at her, her eyes almost completely black and her eyebrows meeting in the middle in a sharp V. Then she walked away. Nora had no idea what she’d done wrong.

Nora tried to forget the janitress’ words. Then Mrs. Ellis accused her of stealing.

“Where’s my brooch with the enamel daffodils? I know you took it.” Firelight reflected in Mrs. Ellis’s gray eyes as she glowered at Nora.

“I did not take it. It must be in your jewelry box. That is where I saw it last.”

Mrs. Ellis grabbed Nora’s wrist. “So you did go through my jewelry box.”

“I didn’t!”

Mrs. Ellis tightened her grip and pulled Nora closer. “Liar.”

“No, ma’am.” Nora shook her head. “I never lie, not ever.”

Mrs. Ellis’s eyes narrowed. Through gritted teeth, she said, “You lie all the time.”

She released Nora’s hand and walked away, leaving Nora to wonder what it was she had supposedly lied about. Later, Nora saw the brooch sitting on the window sill in her room and felt cold all over.

Mrs. Ellis’ accusation was only the beginning. She pulled Nora’s hair, hit her with kitchen spoons, threw books at her. She threatened to drive Nora out into the woods and leave her there or drop her off outside of one of the squalid brothels at the edge of town. Once, she drew an iron poker out of the fire and seared the skin on Nora’s arm with the hot end.

On the day Nora broke free, she was standing outside, underneath the archway. She was hot from the morning’s work and the air there cooled her. She closed her eyes and imagined herself on the sun-warmed deck of a ship, breathing in the briny sea air, on her way home to Galway.

Suddenly, a window opened and Mrs. Ellis leaned out of it.

“Nora, get up here now,” she commanded.

Reluctantly, Nora returned to the apartment. She found Mrs. Ellis standing in the parlor, pointing at her crystal vase.

“It’s chipped. I told you to be careful when you washed it. It was a wedding present. But you’ve ruined it.”

“I don’t see a chip,” Nora replied.

Mrs. Ellis eyes widened. “What is this? Insolence?” Mrs. Ellis slapped Nora’s face. As she put her hand on the hot, stinging welt on her cheek, Nora felt rage surge through her body. With her free hand, she struck Mrs. Ellis, causing her stagger backward in surprise.

Mrs. Ellis reached for one of the fire irons, but Nora snatched the crystal vase and brought it down hard against the other woman’s skull. Nora hit the woman until the every crevice of the cut crystal was covered in blood. Mrs. Ellis slumped to the floor.

Nora’s heart raced. She quickly undressed and tossed her bloodied clothes into the fire. She went into Mrs. Ellis’ closet and hurriedly buttoned herself into a dress of dark blue silk. She stopped to look at her reflection in Mrs. Ellis’ long, gilt-framed mirror. A black velvet hat, amethyst hat pin and lavender gloves made her look like a real lady for once in her life. Nora walked quickly out of the building. She locked eyes with the janitress as she stepped onto the gleaming tiles in the entryway. The janitress nodded and said nothing.

Once she was outside of the Sweet Briar Flats, Nora ran. A young man driving a carriage offered her a ride and she asked him to drop her at the train station. As she waited in line to buy a ticket on the first train going East, she planned her getaway. From New York, she’d sail to Belfast. New York was a three-day trip away by train, but no one would notice her. They’d be looking for a pale servant girl in drab clothes.

Every window slides open at once, sucking in air with a loud yawn. The iron gate shakes, straining against the steel padlock. The gale yanks you off your feet, slamming you against the iron gate and holds you there, flailing your limbs like a turtle on its back. All the breath is knocked out of your lungs. When you try to inhale, you can’t. The part of the gate that is angled to keep people out is bashing the top of your head. Drops of blood speckle your shoulders.

The yawning seems to get louder and louder until it roars like a jet engine. Your whole body vibrates like you’re in the front row at a Metallica concert.

Through the open door, you catch a glimpse of a dark, narrow hallway and the silhouette of a figure standing in it. At first, it looks like a police officer standing with his legs apart, the meager light catching his dangling handcuffs for a split second. Then, it’s a woman in a long skirt wearing a shining pin under her collar. Then, it’s nothing, a flickering light, and EXIT sign with half its letters burnt out.

The door slams shut and the yawning stops. The wind dies down and drops you onto the trash-strewn concrete. You land hard, but you scramble to your feet, not caring that there’s blood on your shirt and a used condom stuck to your back. You gulp in the noxious air; your lungs feel raw, like they’ve been burned.

You turn your back on the Sweet Briar Flats. You run.