You probably know all the classic lines:

“Do you know you look like a little penis with a hat on?”

“You think there are men in this country who ain’t seen your bosoms?”

“What am I supposed to do? Go back to taxi dancing? 10 cents so some slob can sweat gin all over me?”

And of course: “There’s no crying in baseball!”

It’s a fair bet that most of us have seen A League of Their Own, the 1992 film that brought women’s baseball out of the realm of dusty trophies and yellowed newspaper clippings and into the spotlight (not to mention the Baseball Hall of Fame).

Writers who’ve penned nonfiction books about baseball have seen it, too. I won’t name any names, but I’ve read more than one book that addressed the subject of women’s baseball by referring only to the movie. It’s an understandable shortcut, but it’s an unforced error that, perhaps inadvertently, shrinks the history of women’s baseball into a neat 128-minute package and ignores the complexity of the full story.

Here’s one big thing you won’t learn from watching Geena Davis do the splits in her chest protector: The All-American Professional Girls’ Baseball League was not the only game in town.

The National Girls Baseball League

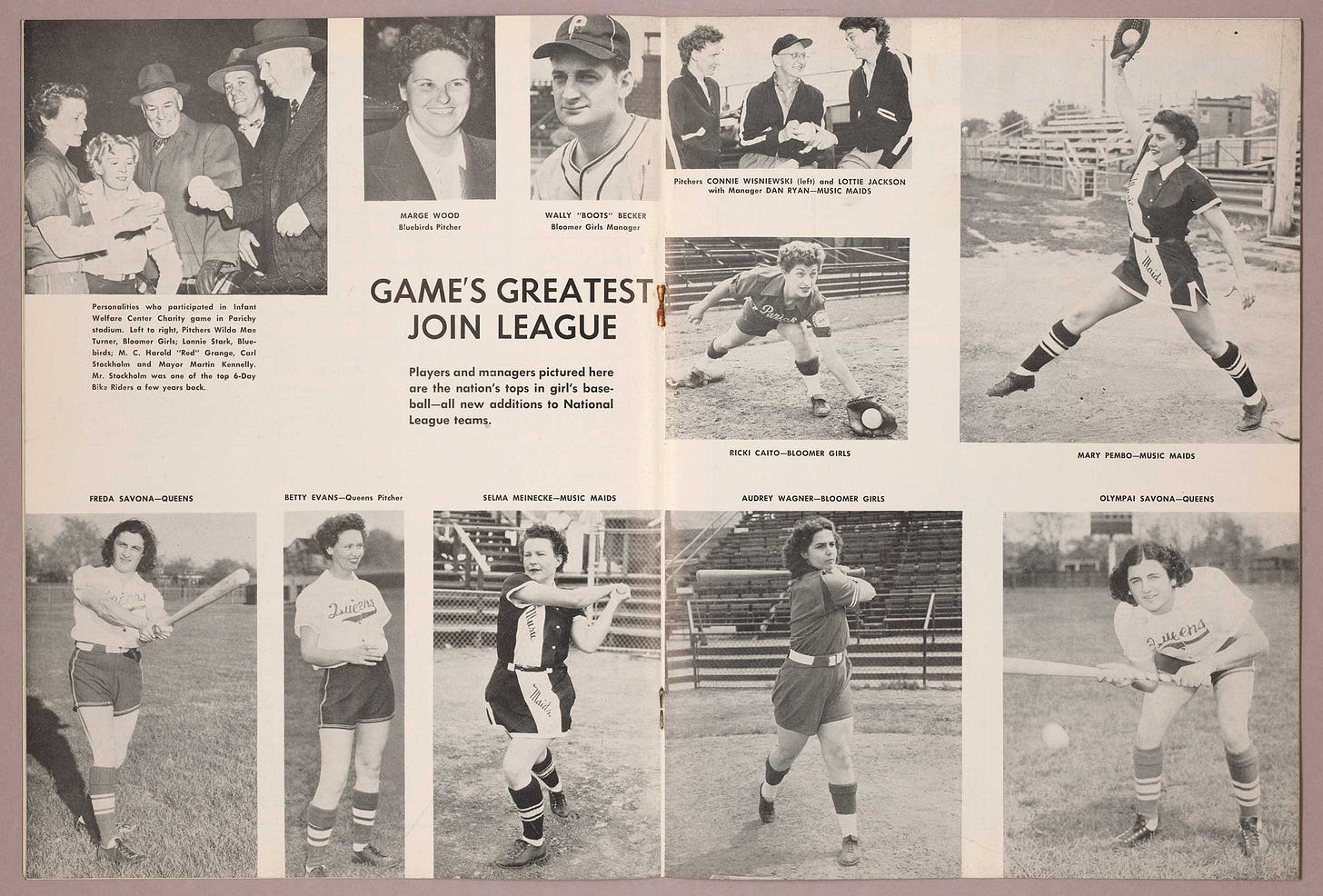

A year after the AAGPBL launched in 1943, a trio of wealthy Chicago men came together to start a rival league: The National Girls Baseball League. Emery Parichy, a contractor from Forest Park, Illinois, enlisted the help of Charles Bidwill and Ed Kolski. Charles Bidwill was a Chicago millionaire heavily invested in sports, including the Chicago Cardinals football team, as well as a racetrack. Ed Kolski was a politician.

Unlike the AAGPBL, which started with teams in four cities and three states (Rockford, Kenosha, Racine and South Bend), the NGBL played exclusively in Chicago and its suburbs. The original teams of the 1944 season were the Bloomer Girls, Bluebirds, Chicks, Kandy Kids and the Sparks. The Bloomer Girls hosted opposing teams at Parichy Memorial Stadium in the suburb of Forest Park, while Bidwill Stadium on 75th Street on Chicago’s South Side was the site of the Bluebirds’ home games.

Coupled with the League’s policy of scheduling night games, the small footprint meant players could hold down day jobs, doubling their earning potential. To top it all off, the NGBL reportedly offered higher salaries. So why didn’t the NGBL hollow out the AAGPBL?

League Raiding

Many players did leave the AAGPBL for the NGBL — and vice versa. An article on the Society for American Baseball Research states:

“From 1944–54 players jumped back and forth between the All-American and National Leagues. Players switched leagues for things like a better salary, playing closer to home and a job—some AAGPBLers didn’t like or got tired of the extended travel—or being more comfortable with one game (usually softball) than the other. Some players in the AAGPBL, especially pitchers and infielders, couldn’t adapt to overhand pitching or throwing the longer field distances that league administration continually adopted, but they were still outstanding softball players. Connie Wisniewski, for instance, first became an AAGPBL outfielder when the increased pitching distance and overhand delivery reduced her pitching effectiveness. In 1950 she switched to the NGBL, where her underhand softball pitching prowess was in demand, but returned to the AAGPBL in 1951 because she enjoyed the social atmosphere there more.”

The article goes on to say that the two leagues came to a “non-raiding” agreement after two years of players treating the leagues like a revolving door. However, according to AAGPBL commissioner Fred K. Leo, the NBPL didn’t hold up its end of the bargain. An article published just before the 1951 season quoted Leo on the matter:

"There are several other girls who are reported to be in the other league who have not reported on time to our clubs for Spring training," Leo said, "and if any of these girls play a single game in another league they'll be given lifetime suspensions from this league," he stated. "The methods being utilized by the National League to lure our players are highly unethical. Recently it was publicly announced that Madeline English of Battle Creek and Dorothy Kamenshek of Rockford were signed to National League teams, but such was not the case. Miss Kamenshek has signed with Rockford and at the time of the announcement the National League could not produce a signed contract for the services of Miss English, either. This kind of operation is certain to bring reprisals from us if the practice is continued," Leo declared.

Say It Ain’t So, Buck

Charles Bidwill owned the Sportsmans Park racetrack, and one of his pari-mutuel clerks was George “Buck” Weaver, the former White Sox third baseman banned from Major League Baseball for life for knowing about, but not participating in, the scheme to throw the 1919 World Series. Bidwill asked Buck to manage one of the new girls’ teams, and so the disgraced third sacker stepped up to lead the Bluebirds.

NGBL players wore satin shorts instead of skirts, but their uniforms exposed just as much skin. While watching the girls slide on gravel with bare legs, Buck said, “Those girls really have it. Why, a ball player won’t hit the dirt unless he has on sliding pads.”

It’s not clear how long Buck managed the Bluebirds. Irving M. Stein’s biography of Buck Weaver, The Ginger Kid: The Buck Weaver Story, briefly mentions that he managed the team in 1944 but gives no end date. Other sources, including those linked to the Society for American Baseball Research, don’t mention his involvement with the Bluebirds at all.

Through my own research, scouring newspaper archives via newspapers.com, I was able to discern that he coached the Bluebirds at least through 1946. In 1952, Buck’s wife, Helen, a former vaudeville star, suffered a stroke. They had no children of their own, but a niece bought them a television, and Buck spent most of his time at home with Helen. It’s plausible that his tenure as Bluebird’s manager ended in 1952, but I haven’t been able to confirm it. The Rare Books and Special Collections Repository at the University of Notre Dame has an extensive collection of NGBL memorabilia, so I’ve reached out to them to see if they can put this question to rest. As of this writing, I’m waiting for a response.

For Buck Weaver, the Bluebirds gave him a connection to the game he loved. On Twitter (back when I was still on it), I mentioned Buck Weaver’s time as the Bluebirds skipper, and some guy said, “That was the only way he could stay connected to the game. That’s really sad.”

Right, because there’s nothing sadder than having to coach a bunch of women. You can’t see it, reader, but I’m rolling my eyes very hard right now.

Dirt in the Shorts

As I mentioned above, the NGBL players didn’t wear skirts, and they didn’t have exhaustive rules about how they could wear their hair, how much lipstick to put on, or whether they could wear jewelry. There was no charm school requirement (to be fair, that only lasted a few seasons for AAGPBLers) and no set of exercises players were required to do to make their eyes brighter. Because the NGBL demphasized looks, the Forest Park Historical Society’s webpage on the Bloomer Girls states, “The NGBL was more about the sport.”

But that’s not entirely true. While the NGBL played softball throughout its run, the AAGPBL gradually evolved from softball to baseball. In addition to the switch from overhand pitching in 1948, the ball shrank to MLB-regulation size, and basepaths eventually lengthened to 85 feet, 5 feet short of MLB’s standard. By 1954, the AAGPBL was playing a more athletically challenging game, which, according to some, was part of the AAGPBL’s demise. (However, when you consider that the NGBL folded the same year, you can make the argument that the increase in televised MLB games was the real culprit.)

A League of Their Own shows the players playing baseball, not softball. It makes sense for the movie, but it’s historically inaccurate, and that matters. The softball style of play is one of the reasons the Minneapolis Millerettes only lasted one year — more on that in a future post.

Integrated Play

Race was a key difference between the two leagues. The AAGPBL was only open to white players (“Canadians, Irish ones and Swedes!”) while the NGBL was integrated. A Wikipedia entry for the NGBL lists several non-white players: “League rosters included an African–American, Betty Chapman; a Chinese–American, Gwen Wong; and Nancy Ito, a Japanese–American.”

The Rare Books and Special Collections site for Notre Dame features an article on the NGBL, which points out that the league had Latina players, but the AAGBPL did too; some AAGBPL players went on exhibition tours in Cuba, and there were a handful of Cuban players in the AAGBPL.

This, boys and girls, is why you cannot treat A League of Their Own as the sum of all wisdom on women’s baseball.

Is Women’s Baseball Coming Back?

The Women’s Pro Baseball League is set to launch in summer 2026, 72 years after both the NGBL and AAGPBL folded. With growing frustration among fans in smaller MLB markets and the commissioner’s and owners’ apparent disdain for fans (not to mention the high cost of attending games), there may be no better time for women to remind us all why we love baseball.

The only movie line I remembered was "no crying". Didn't know of the two competing leagues; it's never a good idea to trust Hollywood to have the facts straight.

Great piece! Tho it does make me want to watch “that movie” again 😉