Picture this: You’ve just dropped a doubleheader to Rockford. You slid hard into second base during the fifth inning of the second game, and now a strawberry the size of a bathmat covers the back of your thigh. It throbs and you can’t stand to sit still, but you have an eight-hour bus ride ahead of you.

Conversation is minimal as the bus rolls through cornfields, because you all know that when you get to what is supposed to be your home turf, you’ll face another sparse crowd — 100 people, if you’re lucky. Fans don’t roar unless it’s for the other team. And to top it all off, some drip at the Minneapolis Star keeps calling you “dainty.”

If this is you, the year is 1944, and you’re a Minneapolis Millerette.

A year after the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League had its inaugural season, the league decided to expand to Minneapolis. Borrowing a name from the long-established local minor league team, the AAGPBL christened the new squad the Millerettes and set them up to play at Nicollet Park, where the Minneapolis Millers had been playing since 1884.

Other cities embraced AAGPBL teams, and crowd sizes grew steadily over time. Minneapolis was a different story. The Millerettes never got off the ground, and by the end of July 1944, the league’s experiment with the North Star State was over.

The Millerettes’ manager blamed a hostile press, but a closer look at history points the finger at the league’s own blunders.

“Millerettes give up,” was the headline in the Minneapolis Star on July 24, 1944. “EVEN THE WEALTHIEST PERSONS will not keep throwing money into a bottomless well forever,” wrote Charles Johnson for his Lowdown on Sports column.

Johnson put the blame squarely on price:

“The biggest mistake the Wrigleys made in Minneapolis was the scale of prices. The games didn't have enough class to be worth a general admission fee of 85 cents, the same as for American Association contests.” (Editor’s note: The Minneapolis Millers were part of the American Association.)

“Wrigley didn't set up the prices without considerable thought. He reasoned that it wouldn't be fair to undersell regular professional baseball. He refused to budge from that stand. That proved his undoing. It wasn't in line with his charges in such cities as Kenosha, Racine, Rockford and South Bend, but the man with the money bags simply wouldn't have it otherwise in the local promotion.

The girls had a chance to get by financially if the admission fee had been set at 50 cents. The games aren't worth more than that and Wrigley now has found it out.”

Talk about your unforced errors.

If it sounds like Johnson was putting down AAGPBL players with his “the games didn’t have enough class” comment, well, he probably was. But the AAGPBL was playing softball in 1944. Its gradual transition to a style of play closer to MLB regulations didn’t begin until 1948.

And Minneapolis had no shortage of softball.

In When Women Played Hardball, Susan E. Johnson argues that there were so many free softball games for Minneapolitans to attend that people had no use for the Millerettes. A look through newspapers from 1943, which published game schedules and results from softball games, makes Ms. Johnson’s claim seem like an understatement.

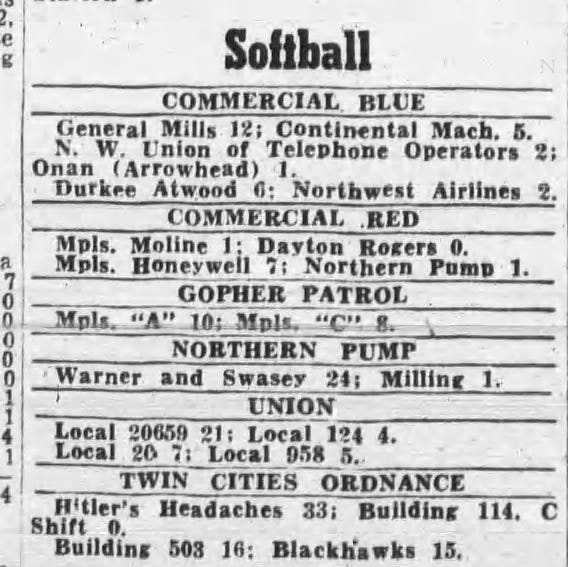

Back then, intramural sports leagues were a benefit that companies offered to their employees as a way to boost morale, and in 1943, nearly every company big enough to assemble a team did.

General Mills. Red Owl. Northwest Airlines. Bernier Jewelry. Smith Welding. Honeywell.

Dayton’s Department store had a team — the Daytonians — and though no hard evidence confirms it, we can infer that Donaldson’s and Power’s had teams, too.

A union league set up contests between collective bargaining units, except for the Telephone Workers’ union. They were in the Commercial Blue league with Durkee Atwood and Continental Machines.

Massive war industry workhorses like the Twin Cities Ordinance Plant and Northern Pump didn’t just have teams; they had leagues of their own. Most of TCOP’s teams had dull names indicating which part of the company the squads hailed from, like “Building 114, C Shift,” or “Bullet shop”. But some players got creative, like the TCOP team that took the field under the name “Hitler’s Headaches.”

On June 5, 1943, the Foundry team from Northern Pump crushed the guys from Gun Mount Assembly, 19-2.

A separate “Girls American” league let women in on the fun. TCOP sent a team called TCOP Monarks to the diamond, and on July 15, 1943, the Monarks issued a humiliating defeat to the team from Honeywell, shutting them out and scoring 23 runs. The league comprised 300 girls.

Why, exactly, did Minneapolis need another softball team?

Both Charles and Susan Johnson left out an additional factor that could have kept fans away from Millerettes games. Minneapolis isn’t exactly a small town, but it’s also not a place where you can disappear into a crowd. And back in the ‘40s, Minneapolis’ communities were tight-knit. If you lived in the city then, you probably knew someone who worked at one of these companies. Wouldn’t you rather take a Hennepin Avenue streetcar to Parade Park and cheer on your friends and colleagues than pay almost a dollar to root for a bunch of girls you’ve never seen before?

Understanding the Millerettes’ failure is simple: the AAGPBL brought an overpriced product to an oversaturated market. No amount of positive press is going to overcome that.

It’s been a while since I read When Women Played Hardball, but if I recall correctly, the book cites misogyny as another roadblock to the team’s success. But why would Minneapolis crowds be any more misogynistic than fans in Rockford, Kenosha or South Bend?

On the contrary, Frank Diamond of the Minneapolis Morning Tribune bubbled with enthusiasm for the local women’s softball teams in his reporting:

“This year AT LEAST 20 TEAMS will battle for glory and physical fitness at the Parade grounds, with no teams hailing from St. Paul. Led by Lorraine Borge, probably the outstanding girl athlete in the state, Minneapolis boasts a number of girls that rank with the best in the country-and that includes the professional league recently organized by William Wrigley, owner of the Chicago Cubs.

Ranging from the ten-year-olds that compete in the junior park league to office managers and war plant foremen, Minneapolis girls are going in for softball in a way that puts the men players to shame.

Out in force even before the snow had melted, the girls are still clamoring for positions on the various teams. And, best of petitioners must be home. They can do the most good.

Some of the veterans have volunteered to coach junior teams and others have signed to umpire in girls leagues in which they do not compete.

The girls have a startling sense of honor in which umpire-baiting is bad taste.

The majority of them refute the old tradition that all female competitors must be homely. In fact, by any standard, a good share of the girls can be considered attractive in addition to boasting poise far beyond their years.

Entered to date in the crack national girls league are the Mirby Sathers and a team composed of former members of the Loring Park and Loring Fur teams. Also, likely entries are teams from a number of war plants.”

By today’s standards, Diamond’s comments about players’ attractiveness seem sexist, but he was refuting a stereotype that was common at the time. At any rate, his comment seems less demeaning than coverage of AAGPBL players that referred to players as “dainty” or “pretty.” But the AAGPBL’s own emphasis on looks and insistence on short skirts invited that sort of commentary. Local girls played in baggy trousers. It’s not terribly surprising that a city full of Lutherans would find the AAGPBL’s tiny hemlines to be a bit…much.

After the Millerettes left Minneapolis, they spent the rest of the 1944 season on the road. At the start of the 1945 season, they had a new home in Fort Wayne, Indiana, and a new name: the Fort Wayne Daisies. Ten years after the Millerettes flopped, the Daisies dominated the AAGPBL’s final season, finishing with a record of 54 - 40, but losing in the playoffs to the second-place Kalamazoo Lassies.

In 1960, the Minneapolis Millers ended their 76-year run after sending players like Ted Williams and Willie Mays to the majors, and made way for the Minnesota Twins. (Any hostility the Millerettes got from the press is nothing compared to what the Twins are currently getting — just sayin.)