Back in the fifties, they called us B-Girls. It was short for Bar Girl, but really, the B could have stood for anything. Plan B, B-side, b-roll, B plus...you get the idea. You can’t have any of those without an A. But there were no A-girls. I suppose the A-girls were the ones who danced on stage, or the women that waited for the men at home. A-girls had their names spelled out in marquee lights or embroidered on monogrammed towels. Nobody cared about our names, but if we were lucky, the bartenders would keep our favorite bar stools free.

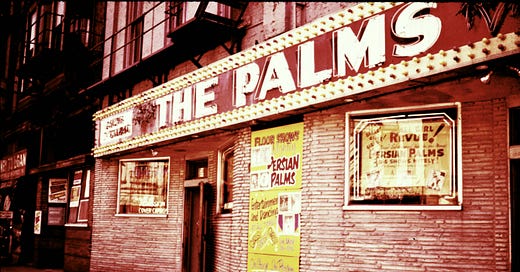

The Persian Palms was on Skid Row, but they always had a few B-Girls on the payroll and it was the best place in town to make a few bucks. Sometimes, we freelanced at other bars -- the dark ones with the broken tiles on the floor and the greasy brass rails -- where the men started drinking at eight in the morning and were already drunk when you got there. It was easy getting their money because you could just roll them, but they were poor to begin with and never worth more than a few dimes. We only did that when we needed a little extra mad money.

The Palms was just as grubby as any of the other places on Skid Row, but it attracted the kind of men who had money and spent it. They came for the floor shows, for the women who danced around naked with big fans made of feathers to hide their bosoms, or the troupes of big fat girls who did the cancan in frilly pinafores, the stage shaking like thunder every time their high kicks came back down to Earth.

The men preferred beer, but beer was cheap, and the Russian who owned the place wanted them to spend more, so our job was to get them to buy us drinks. At the end of the night, he’d hand us envelopes full of cash. If it was a good night, we’d take taxis home. Otherwise, we had to walk several blocks away from the Palms to a corner where we could wait for the streetcar without being pestered by the alkies who lived in the Skid Row flophouses.

I had a red wool suit that I wore with a white silk blouse underneath. It was out of date by about ten years, but I had a red velvet fascinator that matched, with a little beaded mesh veil that came down over my left eye. I would put on red lipstick and step into the Palms at five-thirty, pretending I was a secretary and that I was just stopping for a drink after work. I had blonde hair then, and men would compare me to Mitzi Gaynor if they were fashionable, Joan Fontaine if they were smart, or Marilyn Monroe if they were trying too hard. No matter which starlet’s name came out of their mouths, I knew once they said it that I’d found my mark for the evening.

I remember one night in September, when the air smelled like fresh apples -- except in Skid Row where it smelled like stale smoke and piss -- I took a seat at the bar and ordered a vodka gimlet. Jimmy, the bartender, handed me a glass of water with a lime wheel. He nodded toward a man sitting at the other end of the bar. He wore a Navy uniform. The patch on his shoulder had three gold chevrons and a star on top. That meant that he was a Senior Chief Petty Officer and was probably only in town for a few days. Both of those things meant he had money and would spend it.

On the jukebox, Cathy Carr sang “Ivory Tower” over a tinkling piano and a moaning accordion. I threw glances over my shoulder until I caught the sailor’s eye. He had red hair under his cap, and freckles, but his face was tanned, probably from standing at attention for hours on a flight deck under searing ocean sun. When he finally looked my way, I noticed that his eyes were as green as the sun shining through maple leaves. He flushed a little and looked away.

This will be easy, I thought. It always surprised me when servicemen didn’t seem to know any better. Often, they learned lessons the hard way in foreign ports of call where girls like me would dose them and rob them blind, but men could always be counted on to lose their common sense where a pretty face was concerned. I was never all that pretty, but that never mattered either. You just had to be young.

He got up from his bar stool and came over to talk to me, leaning one elbow on the bar and clutching a beer in his hand. He asked me my name, and I told him it was Misty even though it wasn’t, and he said his name was Rudolph.

“Oh? Like Rudolph Valentino?” I said

“Who’s he?” the sailor asked. “A baseball player?”

I faked a laugh. If he were older, he’d have known that the invocation of the swarthy Italian actor was a come-on, but the sailor must have been too young to remember The Sheik or Blood and Sand or any of those other silent movies. I had never seen them either, but my mother had loved Valentino and always said she wished she could have been an actress and starred in films alongside him.

He asked me what I did for a living so I told him I was a stenographer at one of the flour mills down by the river and that I’d had such a long day. The truth was that I’d slept until two in the afternoon and spent three hours making myself look like I’d been taking shorthand all day.

I told him I wanted to hear about all of his adventures in the Navy, so he started telling me about the time he almost fell asleep while he was on watch and snapped to attention just before his commanding officer walked up behind him. I touched his arm and kept my eye on his beer. If I suggested champagne while he still had half a beer, he’d hesitate, and if I waited until the bottle was empty, he’d order another beer before I got the chance.

The bar was starting to fill up. One of the floor shows was scheduled to start within the hour. The pegboard outside the front door advertised Divena, a stripper whose gimmick was wriggling out of her clothes while underwater in a giant fish tank. I’d seen her before, kicking her legs to keep from bobbing to the top, her cheeks puffed out like a goldfish as she struggled to pull her arm out of a wet shirt sleeve. When she was finished, her clothes floated on top of the tank while she wore tiny satin briefs and celluloid pasties in the shape of seashells.

A Dean Martin bolero came on the jukebox and I mindlessly tapped my fingers along to the sound of the castanets and Spanish guitar.

“Do you want to dance?” the sailor asked.

“Oh,” I turned halfway away, hiding my cheek behind my shoulder and batting my mascaraed lashes, “I might need a little champagne first.”

The sailor signaled to Jimmy who set two champagne flutes -- which held a pint of champagne each -- and poured the pale, shimmering liquid. B-girls often drank fake cocktails while their marks got blotto on the real stuff, but I could put away glass after glass of champagne without feeling the least bit tipsy while my dates slurred and sweated.

As I brought the champagne flute to my lips, I locked eyes with the sailor and let the bubbles tickle my lips. He took a big swig and then turned his head to the side and started hacking. I patted his knee as he cleared the liquid out of his airway and made a joke about the champagne having bones in it.

On stage, the microphone crackled. A short guy in a brown suit walked out onto the stage. He was a comedian who MC'd the shows at the Palms and told jokes between the acts. He often drank glasses of whiskey before he got on stage and by the end of the night got so drunk, he’d spend the night in one of the cage hotels on Skid Row instead of driving home to his wife and their leafy yard.

“I’m sorry to announce that Divena won’t be appearing tonight,” the comedian said, followed by a groan of disappointment from the crowd. “They found a crack in her fishtank earlier today. They tried putting tape over it, but the Persian Palms doesn’t have flood insurance, so the show must go off.”

A smattering of laughter rose from the crowd.

“But never fear, folks. We’ve still got a great show for you today. When we heard Divena was out, we put in a call to the Beef Trust Chorus, and they agreed to sacrifice their day off in exchange for fifty bucks worth of ham.”

The curtain behind the stage rustled, and Maxine, the Beef Trust dance captain, poked her head through, still wearing curlers in her auburn hair.

“That’s fifty bucks and a ham!” she shouted, and disappeared behind the curtain. The crowd laughed and the sailor laughed too. That’s one thing you could say about the Beef Trust girls. They were good sports. They also made a lot more money than I did -- one hundred dollars a week. I was lucky to make fifty. To top it off, they never lacked for marriage proposals -- and not from lardos, either. Maxine was married to a handsome guitar player who had the body of a prize fighter. I would’ve traded places with her in an instant, even if it meant saying goodbye to my twenty-four inch waist.

I felt the sailor’s hand on my wrist -- my cue to finish the last of my champagne. He signaled to Jimmy who refilled our glasses. By the time Jimmy poured us our third split, the sailor’s eyes were starting to roll back and the top half of his body swayed. Jimmy and I traded glances.

“Maybe we should go someplace quieter,” I said in my best Lauren Bacall voice. The sailor opened his wallet and fumbled for a few bills. One of them fell to the floor before he could set it on the bar. I bent to pick it up and slipped it into the sleeve of my suit jacket. I noticed how shiny his shoes were.

As Jimmy put the sailor’s cash in the register, I let the sailor put his arm around me. His legs wobbled as we exited the bar into the cool evening air. We walked across the street to a park, a big grass triangle with “boulders” that were really just the snoring bodies of other passed-out drunks.

I helped the sailor down onto a bench and let him kiss and paw at me for a while. By the way he was breathing, I knew he would pass out soon. Finally, he slumped backward, his arm dangling over the armrest. I quickly got up and went back into the Palms. In the Ladies’ room, I pulled down my hose and released a flood of used champagne. Then, I peered into the mirror, which was covered in fingerprints, and put on a fresh coat of lipstick. I smoothed my hair and repinned my fascinator.

On stage, the Beef Trust Chorus girls were all in formation, with their arms across each other’s shoulders, kicking like Rockettes. They were all smiling. The men in the crowd clapped and whistled.

I glanced at Jimmy who nodded toward a man who was sitting alone at a table near the stage. I pulled out the chair next to the man and sat down.

“Hey honey,” I said, “buy me a drink?”

He turned slowly. He had a black, pencil-thin mustache above his lip and dark hair full of Brylcreem. I noticed his onyx cufflinks and his silver tie pin. He looked me over and his lip curled.

“You look old enough to buy your own,” he said.

At the end of the night, Jimmy handed me an envelope with eight dollars in it. It was less than half of what I’d hoped to earn that night. I considered heading over to the Valhalla or the Sourdough, or any of the other places where old men went to stave off the DTs, but I still had the sailor’s dollar, which was worth as much as I would get from pickpocketing.

I set out for the streetcar. As I crossed the street, I saw that the sailor was still sitting on the park bench, only he had come out of his stupor and was sitting with his head in his hands. I picked up the pace so he wouldn’t notice me, but as I walked past him, I heard sniffling. I realized that he was crying.

A few years later, when the city tore down Skid Row and made it into parking lots, I gave up the B-Girl grift. I got a job as a waitress in a diner where I worked long hours for the same amount of money, and I got sore feet instead of champagne. Occasionally, men said things like, “Didn’t I buy you drinks once at the Persian Palms?” I always told them they were mistaken, but they would watch me carefully, and then leave very small tips.

After all these years, there isn’t much I remember about being a B-girl. Sometimes, though, I think back to that September night and the crying sailor on the park bench. I try to imagine what it was like for him to wake up in the cold and realize that the space next to him was empty.

There is one thing I do remember. I remember the pin I bought with the sailor’s dollar. It was gold-plated and shaped like an angel. I pinned it to the collar on my winter coat. Every day, for several Februaries, that angel remained pinned to my coat, even as the wool became threadbare and the silk lining shredded.

The last February I wore it was the one when the Beatles came for the first time. The Monday after they appeared on Ed Sullivan, I ran for the bus. The pin came loose and fell into the snow. I stopped to search for it. The snow melted under my fingers. I saw a shimmer of gold but it turned out to be a cellophane candy wrapper. Behind me, I heard the sound of the bus approaching.

I left the angel behind.

Author’s note: This story is part of a series I did on the Gateway District — Minneapolis’ Skid Row — in the 1950s. My story, The Pioneer Hotel, appeared in Lowestoft Chronicle in 2020. More in this series coming soon!

So good!

I love the recurring characters!!