Revolver to Her Head

Explore a Minneapolis case that exposed misogyny in the justice system and a killer's desperate attempt to evade justice.

On the night of September 27, 1906, Henry Sussman arrived at the Nashville Hotel at 422 Hennepin Avenue and registered as Joe Weller. He then entered a second-floor room, turned on the gas jets on a five-burner chandelier and, as the Star Tribune put it, “retired, never expecting again to see daylight.”

He had good reason for wanting to drift away peacefully: he’d murdered his wife at another hotel just one day prior. But Sussman wouldn’t be so lucky.

After a few false leads, police tracked Sussman down at the Nashville in the early morning hours of Friday, September 28. When they smelled the strong odor of gas coming from his room, they obtained a key from the front desk. Gagging on fumes, the police “managed to grope their way to the bed and grasp the form of the man who was lying on it.” They dragged Sussman out into the hallway and revived him. Had the police arrived one hour later, the newspaper reported, Sussman would’ve been dead.

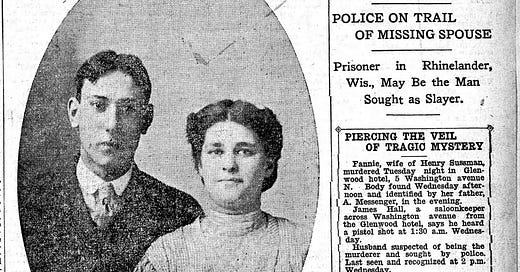

After police resuscitated him, Sussman confessed that he shot his wife, Fannie, at the Glenwood Hotel on September 25.

An unhappy marriage

Fannie and Henry married when they were just sixteen years old, and the marriage was not a happy one. (Some reports say they were married for four years, while court transcripts recreated in newspapers show that the marriage lasted one and a half years.) After marrying Fannie, he joined the army, possibly as a means of running out on her. During his trial, the state’s attorney demanded to know why Henry claimed to send letters from Ohio when they appeared to have been written in Syracuse, New York. He told Fannie not to write him until he had an address in Canada, and then he never sent her any address.

On April 27, 1906, Sussman was arraigned for “non-support.” Fannie testified that he “failed to furnish her with food and clothes.” He frequently returned home in an “ugly mood” and drove her from the house. He beat her “time after time.”

A judge sentenced Henry to 35 days in the workhouse and offered to stay his sentence if he could pay a $200 bond. Henry couldn’t come up with the cash, so he did time. In the workhouse, his resentment grew, and he vowed revenge against poor Fannie.

A wanted man

His arraignment for non-support was not Henry’s only legal trouble. During his stint in the army, he was court-martialed for allowing prisoners to escape while he was on guard. At the time of Fannie’s murder, he was wanted in Wisconsin for forgery after putting a business partner’s name on a money order. He would later claim that he asked Fannie to go with him to La Crosse to testify on his behalf, but she refused, and inflamed his rage, sparking his crime of passion.

Revolver to her head

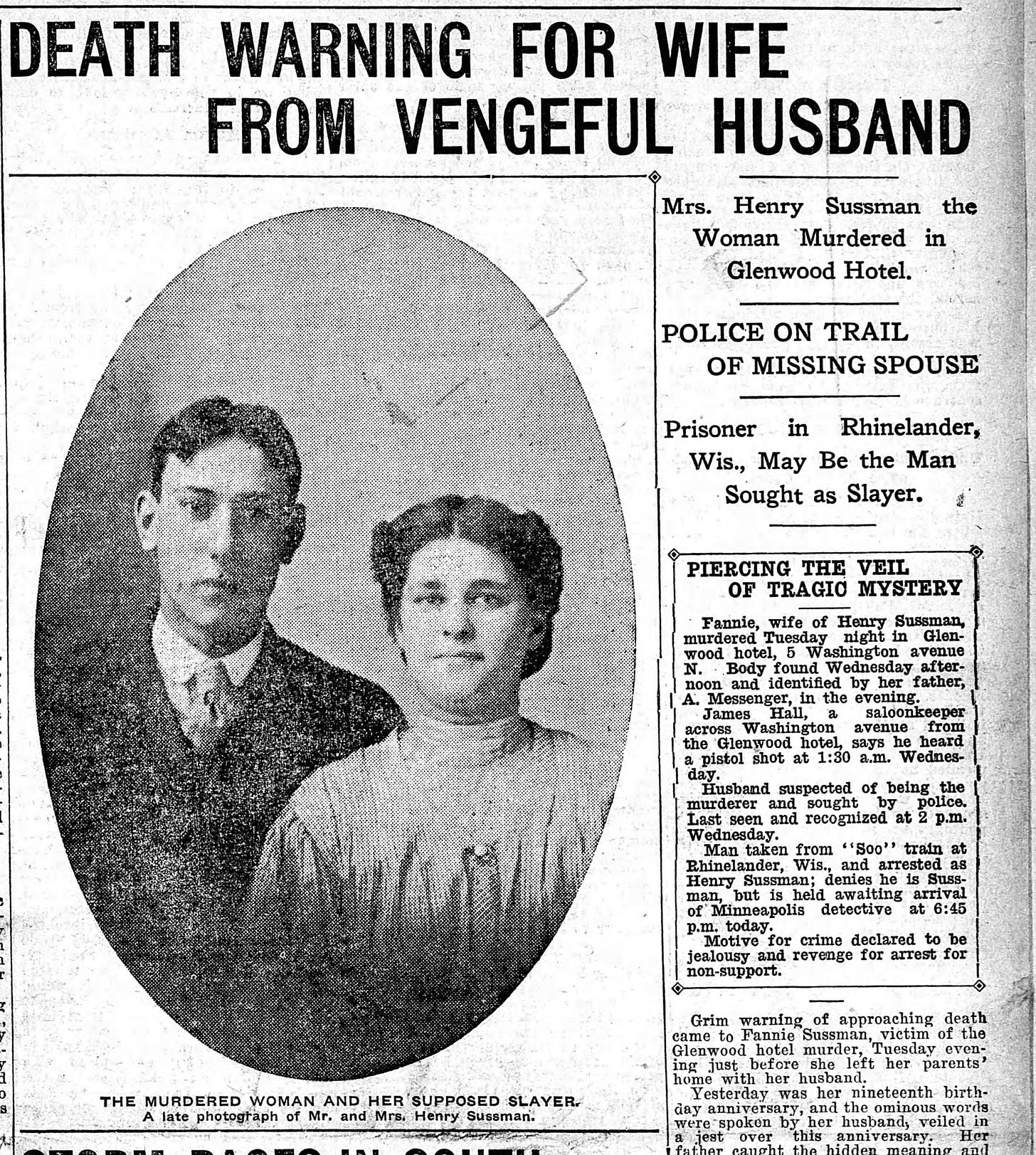

Fannie’s father had warned her not to see Henry that night, but because she possessed what the newspapers called “a love that conquered all fear,” she went anyway. Henry took her to a show at the Bijou Theatre. Henry didn’t like the show, so they left before the end of the second half and went across the street to the Glenwood Hotel, where they argued for hours. Henry would later tell the court that she’d told him to “go to the dogs” and that she didn’t want to be his wife anymore. She wasn’t going to help him with his Wisconsin legal troubles, either. (The state’s attorney would later reveal that she had, in fact, written a letter to the Wisconsin judge, asking for clemency for her husband.)

The Minneapolis Journal published this account of the killing:

“Anger made him cool. He placed the revolver to her head so that the bullet would take a downward course. He was determined and his hand was steady. He pulled the trigger, the revolver discharged with a loud report, and the victim, his wife, fell over on the bed. A slight gasp and she was dead.

Laying the dead body straight on the bed, he placed the revolver in his pocket and walked down the stairs to the street. The exact time of the murder, as near as Sussman can put it, was 6:30 a.m. on Wednesday.”

Henry gave a slightly different version on the witness stand:

“I remember getting the gun somehow and the shot being fired. I don’t know where I stood or how I got the gun. I was nervous and excited and I don’t know just what happened.”

A chambermaid found Fannie that morning. Believing Fannie was still asleep, the maid pulled down the window shade to keep the sun off her face. When she realized the woman was dead, she rushed to tell the hotel proprietor, who informed the police. Fannie’s father identified her body at the morgue.

Meanwhile, Henry took himself out drinking at Hookwith’s Saloon on Nicollet Avenue, and then to Regan’s restaurant for lunch.

The “loud report” in the Journal’s version may have been a bit of sensationalism, as most other reports said no one in the hotel heard the gunshot. The Star Tribune article that reported on Sussman’s suicide attempt said a nearby bartender claimed to hear the shot, but he put the sound at around 1 a.m., and Sussman’s confession put Fannie’s time of death much later than that.

What’s a murder story without at least one red herring?

“First of all, she was a whore…”

Soprano’s fans will recall Ralph Cifaretto’s savage beating of his girlfriend, Tracy. His justification: “She was a whore and that wasn’t my kid she was carrying.” Henry Sussman could’ve been the inspiration for this story arc. A witness for the defense at Henry’s trial said Fannie was “an inmate at no less than three houses of evil repute in St. Paul,” and that she “consorted under assumed names with persons of bad character.” (On cross-examination, the prosecutor called into question the witness’s character by goading him into admitting he was related to a brass thief.)

Henry’s brother also testified that he was a stand-up citizen until she came along.

During his own turn in the stand, Henry claimed Fannie told him she’d been with four or five men in Duluth, had “made a lot of money and had a good time.”

As the trial wound to a close, newspapers reported that the defense was “satisfied” that they’d proved Fannie was “not a true wife” and that an “unwritten law” would save Henry from the gallows. While the articles did not explicitly state what the “unwritten law” was, it seems to have been the Ralph Cifaretto ethos: it’s justifiable to murder a woman if she’s a whore and pregnant with somebody else’s baby.

Other “disinterested” attorneys who talked to reporters said that the “unwritten law” didn’t “stretch that far,” especially because Henry said “everything would be fine” if she went to La Crosse to testify. In other words, he didn’t care about the houses of evil repute where she allegedly worked, or about the other men she consorted with. He cared about her ability to save his hide, and therefore, the unwritten law didn’t apply.

No gallows

In the end, Henry Sussman didn’t go to the gallows. The jury let him off for murder one, but convicted him of second-degree murder. If it seems unjust on its face, remember that he tried to kill himself before police dragged him out of a self-made gas chamber and made him face his crimes. Serving a life sentence at Stillwater Prison may well be the justice he truly deserved.

The judge’s final word

From the bench, the judge delivered this scathing message as he handed down a life sentence:

“While the evidence is clear in my mind, I desire to state that the circumstances surrounding the killing by you of your wife have tended greatly to aggravate your crime, and I do not see in any way in your case that the punishment fixed for the crime of which you have been convicted should to any extent be mitigated or lessened.”

So much for the unwritten law.