Goodbye, Dad: End of the Line

Reflections on cancer, death and the music that helps us grieve.

Author’s note: Saturday, March 9 marked the third anniversary of my father’s death from cancer. The following piece was initially published exclusively in print in Teatles, a Beatles fan zine published in Liverpool, U.K. This version has been edited to include more details about the recording artists mentioned herein, and the Vietnam War. As it happens, my dad’s uncle, Art Maxwell, passed away on March 9, 2024. In a way, this one’s for him too.

When my mom first told me about the tumor behind my dad’s eye, I was listening to the Traveling Wilburys. (In case you’ve never heard of them, the Traveling Wilburys formed in the 1980s and was a collection of aging rockstars, including Bob Dylan, Roy Orbison, Tom Petty, Jeff Lynne, and, most notably, George Harrison, ex-Beatle.) I burst into tears as “End of the Line” started up. A tumor behind his eye? I knew, then, that this would be the end of the line for my dad. I mean, I didn’t know. But I knew.

I replayed the track over and over, paying close attention to George Harrison’s voice as he sang, “Well, it's all right if you live the life you please.” I watched the video and choked up all over again when the camera cut close in on the image of Roy Orbison, who died before the music video was made.

My dad’s cancer started longer ago than I remember. I remember it as starting in 2014 when he first underwent chemo, but it began before that, in 2010. He and my mom had been traveling cross-country by motorcycle, and my dad had what he thought was a burn from the tailpipe on his leg. When it didn’t go away, he had it checked out, and it turned out to be a cancerous tumor.

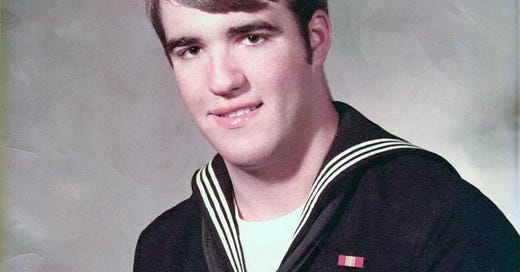

My dad had a rare form of cutaneous lymphoma. We aren’t sure what caused it, but it could have been something he was exposed to in the Navy. Though he didn’t fight in Vietnam, he did serve during that era and could have come into contact with all kinds of chemical agents.

During the Vietnam War, the United States military sprayed 20,000,000 gallons of herbicides over Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos in what was known as Operation Ranch Hand. The “rainbow herbicides” -- the most notorious of which was Agent Orange -- destroyed crops and deprived the enemy of tactical cover. They also contained dioxin, a highly toxic chemical that caused illnesses and birth defects in millions of Vietnamese people and thousands of U.S. servicemen.

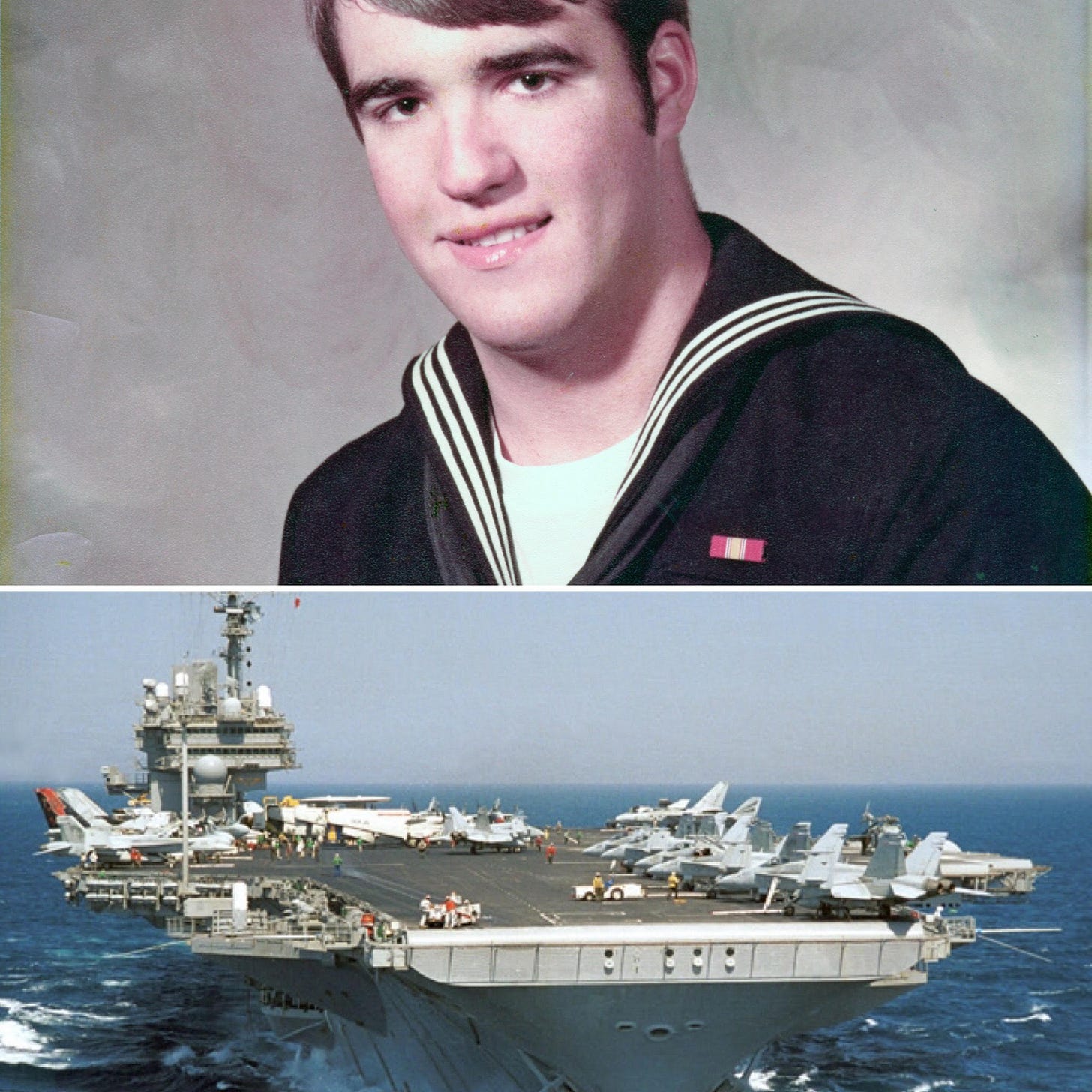

Operation Ranch Hand ended sometime in 1971, the same year my dad enlisted in the Navy, but the aircraft remained in use. Whether any aircraft from Operation Ranch Hand landed on the flight deck of the U.S.S. Kittyhawk while my dad was on board working as an avionics technician in the 1970s is unknown to us. However, a study confirmed that servicemen who flew and maintained the aircraft were exposed to dioxin, even long after the lethal mission had ended.

In the list of debilitating diseases that dioxin causes, the word “lymphoma” appears over and over again.

After chemotherapy and radiation, the doctors said my dad was in remission. His beard and eyebrows grew back. Occasionally, the sores on his legs reappeared. The oncologist sent him directly to the radiologist for treatment. It seemed like this was all behind us until he discovered a new, inoperable tumor in his thigh. Then, he had problems with his vision and began wearing an eye patch. That’s when they found the tumor behind his eye and lymphoma in his spinal fluid.

With treatment, the tumor behind his eye disappeared, and the lymphoma vanished from his spinal fluid. Complications from treatment sent him to the hospital on four different occasions in 2020, but for a brief moment, it seemed like he had turned the corner. He was no longer spending whole afternoons watching Westerns. He was making progress with physical therapy and even started a new batch of home-brewed beer, which has been a hobby of his for several years.

Then suddenly, he rapidly declined. Just a few days before this writing, he and my mother visited the oncologist: the cancer was everywhere. The oncologist gave him a month to live.

Upon hearing this news, I went home and watched A Hard Day's Night, reciting every line in my head a beat before the actors actually said them.

As it turned out, that month was optimistic. Four days after the oncologist told my dad his illness was terminal, I received a text from my mother: “The nurse says he’s in transition and you should come over today while he can still talk.”

I took the day off from work. I rode the bus to my parent’s house. I could have summoned an Uber, but I admit that part of me wanted to stall -- to stretch out the trip and delay the moment when I would see my father in a hospital bed. On the ride over, I listened to the Beatles and George Harrison solo songs that I knew would offer comfort, like “Here Comes the Sun,” “All Things Must Pass,” and, “End of the Line.”

Then suddenly, he rapidly declined. Just a few days before this writing, he and my mother visited the oncologist: the cancer was everywhere.

Cancer touched all of the Beatles’ lives in one form or another. Paul McCartney lost his mother, Mary, to breast cancer when he was fourteen. 42 years later, his wife, Linda, died of the same disease. Ringo’s daughter, Lee, survived brain tumors, while his first wife and Lee’s mother Maureen died of Leukemia. John’s first wife, Cynthia, died of cancer at age 75. And George not only lost his mother to cancer, he died of it himself in 2001.

Until my dad passed, I always thought stories about cancer were boring. It is, after all, so very ordinary -- just look at how much of it there was in the lives of the Beatles’ families! But the experience is anything but ordinary, especially when a person’s life expectancy suddenly gets shorter and shorter like a tunnel of light shrinking down to the size of a pinhole and threatening to flicker out into complete darkness.

At a time like this, I found comfort in music made by four extraordinary individuals. As I waited for the bus to take me to my parents’ house, I remembered Paul’s comments in The Beatles Anthology:

I’m really glad that most of [our] songs dealt with love, peace, understanding. There’s hardly any one of them that says: ‘Go on, kids, tell them all to sod off. Leave your parents.’ It’s all very ‘All You Need Is Love’ or John’s ‘Give Peace a Chance.’ There was a good spirit behind it all, which I’m very proud of.

As others have noted, this is the reason for the longevity of the Beatles’ music, but it’s not just because the music has a good spirit. We still love the Beatles today because it provides us with that good spirit when we need it. Just like the lines we can recite from A Hard Day’s Night, the music gives us a shortcut to the emotions we want to feel. We know we’re going to feel better when we hear the opening chords to a song that has already reminded us that it’s not always going to be this gray.

I replayed the track over and over, paying close attention to George Harrison’s voice as he sang, “Well, it's all right if you live the life you please.”

When I arrived at my parent’s house, the first thing I noticed was a rocking chair that is normally in the living room sitting on the back porch. I knew that meant it had been moved out of the way to make room for the hospital bed Dad was now lying in.

The hospital bed was brown, and it looked old. I recognized the red sheets; they used to be on the twin bed in my childhood room. I asked Dad how he was feeling, but I couldn’t understand his answer until Mom translated: he couldn’t find any baseball on TV. He was looking for a Twins game; Major League Baseball was in Spring Training. My mom had hoped Dad would hang on long enough to watch the Twins home opener with me in April. It had seemed possible four days prior.

“I don’t think they’re playing today,” I said. “Tomorrow, I think.”

He seemed to want to change the channel. Bizarrely, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine was playing on BBC America. I offered him help and he let go of the remote. I found an episode of Gunsmoke.

He fell asleep after that. My mom tried a few times to wake him, but he remained asleep. Before I left, I hugged him. I whispered: “Goodbye, Dad.” The fluid in his chest gurgled and I worried I’d hugged him too tight. He didn’t wake up.

All I wanted to do was go home, cry, and listen to The Traveling Wilburys singing “End of the Line.” Just before midnight that night, I received a text from my mom telling me that my dad had passed away.

“It’s all right, even when they say you’re wrong,” sings Jeff Lynne in “End of the Line.” “It’s all right -- sometimes you gotta be strong.”

Thank you for sharing. I lost both my parents to Pancreatic Cancer. Mom in '01 at age 58, Dad in '21 at age 79. Both went rapidly, but differently - Mom wasn't old, Dad was. Both experiences were awful. The ONLY silver lining to how quickly the went is that they did not suffer long. Mere months. For that, I am grateful.