First Love

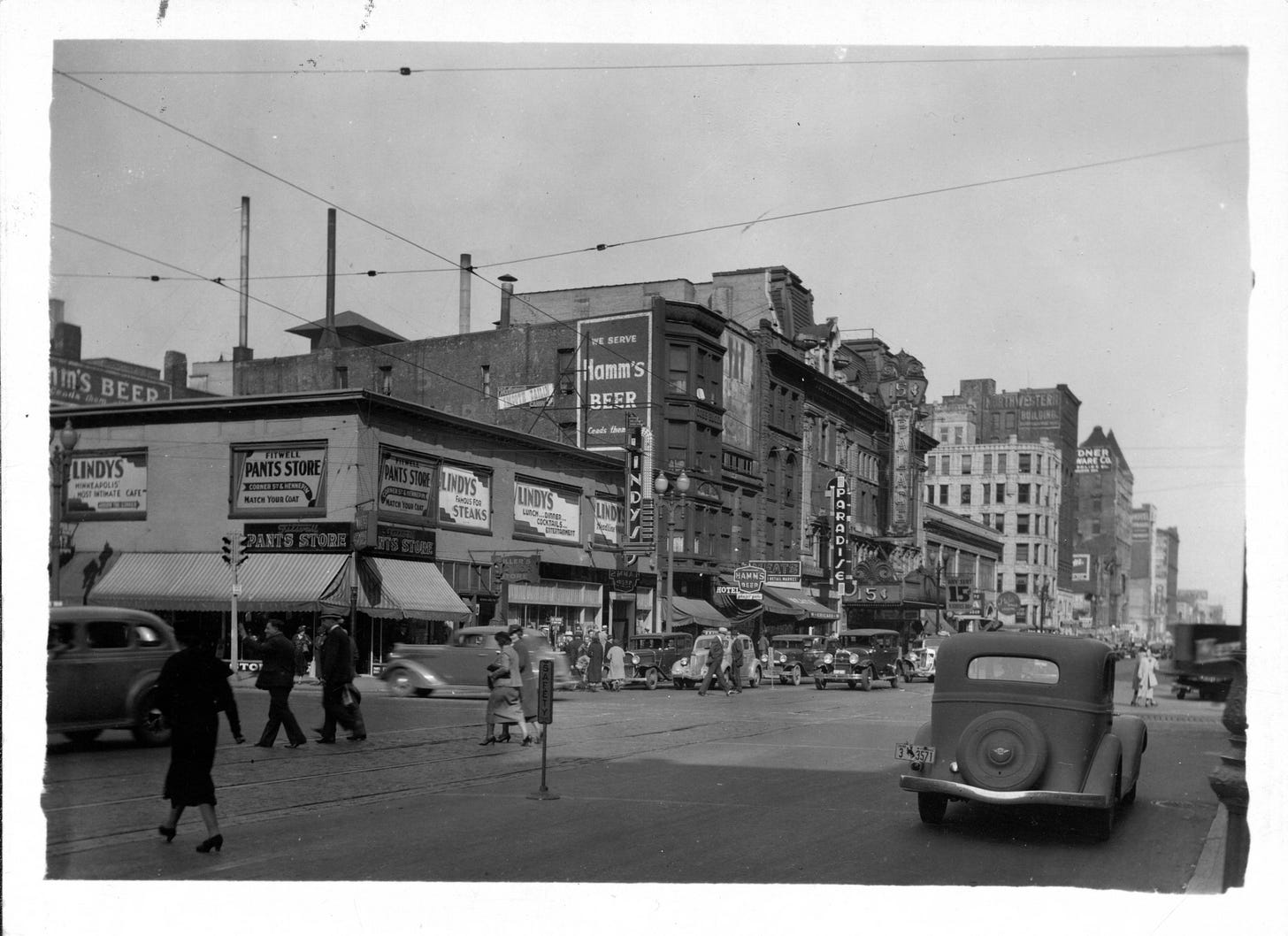

Minneapolis, 1938

“Frenchy won’t dime,” Mickey said, a cigarette clenched between his teeth as he rearranged the cards he held in hand. Wispy white hairs stood up from his balding scalp like ghosts escaping from a neglected crypt. He ran his hand over it, but that just made the hairs stand up even higher.

“I don’t know, Mick,” Archie replied as he tossed another chip into the pile in the middle of the table, “I think you’re wrong.”

Wally laughed and drained a bottle of Gluek’s beer before snatching another from the ice-filled bucket on the floor. “Oh, come on, Arch. You think she’ll turn state’s evidence? The only thing that woman turns is tricks.”

The men laughed. Stasiu, the young stockboy who still wore his smock even though the store had been closed for hours, pried the top off a bottle of beer. “Frenchy’s no rat,” he said. A faint impression of a dark mustache was making a reticent debut on his upper lip.

“What do you know about Frenchy, Stas?” Archie laughed, cigar smoke jetting from his nose.

“I’ve met her,” Stasiu said defensively.

“Not at the Van Dyke,” Mickey said. “If she let you in the Van Dyke, I’ll eat my hat.”

“I have so been inside the Van Dyke,” Stasiu said, straightening his skinny frame. He was tall when he didn’t slouch, but his bones were still green, like saplings, and didn’t take too well to standing up straight for too long.

“When?” Mickey demanded.

“When I delivered her bourbon,” the boy said.

Wally slapped his knee and said, “Is that all you delivered to her?”

Stasiu blushed. “You were there, Wally,” he said, quietly.

Mickey shook his head. “Frenchy Ryan may run the most squalid bordello west of Detroit, but even she doesn’t let innocent young boys like you get past the parlor.” Mickey looked at his cards again and then grunted in disgust. “I’m out,” he said, throwing his cards down onto the table.

“I’m in,” said Archie.

“Not me,” Wally muttered. “I fold.”

“I’m in, too,” Stasiu said.

“You sure about that, kid?” Archie asked. Stasiu nodded coolly. Archie studied the boy’s soft, unlined face and the way his fingers drummed absently on the table.

“Must be good,” Archie said. “I fold. Show us what you got.”

Stasiu’s expression remained unchanged as he flipped over his cards. 2 of clubs. 4 of spades. 6 of diamonds. 8 of clubs. Queen of diamonds.

Archie groaned and covered his face with both hands. He flipped over his cards to reveal a flush, a handful of hearts.

“Well, would you look at that,” Mickey said. “The kid can bluff.”

After the game, Stasiu collected his winnings and sprinted over to Hennepin Avenue to catch the last streetcar of the night. He dropped onto a wooden seat and rested his head against the window. Just before the streetcar pulled away, he glanced through the window at the Van Dyke hotel. The darkness obscured its grimy facade, but the bay windows were lit on all three floors. The place had been raided just a few days ago, but Frenchy had it back up and running in less than a day.

Stasiu glanced up at the window on the top floor and saw a girl’s face, staring back at him, half glowing in the light, half shadowed in darkness. An oval face with a little rosebud mouth, and long, undone hair that was either red or brown -- it was too dark to tell.

The streetcar lurched forward and the Van Dyke disappeared from view. Stasiu shut his eyes. When he and Wally went to the Van Dyke to deliver Frenchy’s liquor, a wild-haired girl lounged on one of the velvet settees, the top of her robe undone and her bosoms hanging out before God and everybody. One of them had a red mark just above the nipple, as if someone had bitten her. When she caught Stasiu looking, she winked. It was mid-afternoon, but the dusty parlor curtains were closed. An old combination gas and electric chandelier hung from the ceiling, its brass arms covered in patches of blueish green. The electric bulbs gave off weak light while the gas jets collected dust. When they left, Wally told him that only the parlor floor had electricity. The other floors still had gaslight.

Stasiu dozed as the streetcar clattered over the tracks that crossed the river. He woke just as it passed Holy Cross on University Avenue and rang for the stop. He heard the distant sound of a small dog barking as he stepped off onto the sidewalk -- the little rat terrier that belonged to the Elias family who lived in a green house across the street from the Maronite church. It always snarled and poked its white nose through the fence whenever Stasiu happened to walk by.

As he walked down 17th street and cut through the alley, a rabbit flattened its body and squeezed under old Mrs. Nowak’s garden gate. Moonlight caught the curves of the watermelons that swelled in her raised garden beds.

When he reached his own yard, he opened the gate slowly so the rusted hinges wouldn’t wake anyone in the house. In the kitchen, the new refrigerator -- which he’d helped buy with money he made at the liquor store -- hummed assertively. Stasiu opened it and his mother’s cast iron skillet full of the sauerkraut pierogies that she’d sauteed with onions for the rest of the family’s dinner. He took the skillet and set it on the kitchen table where he ate with his fingers. No sense dirtying a plate at this hour. As he ate, he thought about the face in window, the girl who had only half of the light on her side. Maybe he’d see her the next time he and Wally made a delivery to the Van Dyke…if the cops didn’t padlock it first.

At the Van Dyke, Clara watched the sun rise over the Mississippi and pulled the curtains shut. The glaring dawn light on the river was too bright for sleeping and it had been a long night. But not because of the johns -- the Van Dyke was the sort of place men wanted to get in and out of as quickly as possible -- but because of Frenchy, who called a meeting after the last client left at 2:00 a.m. and told the girls she was thinking of packing up the whole operation and moving to someplace in South Dakota. Yankton, she said. Then Arabella made a joke about yanking, and the girls fell off the beat-up settees, laughing.

“They’re on to the vice squad,” Frenchy said. “Somebody tipped off the state’s attorney that the vice squad has been leaving us alone. Of course, all they have right now is hearsay. They don’t know anything unless they hear it from me, and I’m not going to say a word. And you all better not be saying a word, neither.”

Clara shifted in her seat as Frenchy stared at her and the rest of the girls in turn. How could Frenchy think any of the girls would say anything -- especially if that meant moving to a one-horse town like Yankton? The Van Dyke wasn’t much, with its narrow staircases, cramped hallways and ancient flaming gasoliers, but there were movie theaters nearby, and the river, chow mein at Nankin. Clara didn’t know, but she didn’t expect to find those things out on the Dakota prairie.

After the meeting, Clara said to Arabella, “She can’t really think it was one of us who told, can she?”

Arabella just shrugged. “She can think what she wants, but it’s not like any of us knows. We don’t know who she pays that hush money to, or how much. We just know they stopped beating down the door and dragging us down to the county jail in the middle of the night.”

“For now,” Clara replied.

“You worry too much.” Arabella pulled a small silver flask from a hidden pocket she’d sewn into her silk kimono. “Have a nip,” she said.

Clara took a sip and quickly handed it back. The bourbon burned the back of her throat. It was the good bourbon that Frenchy saved for the clients -- the rich ones who came by once or twice a week.

“You’re siphoning off Frenchy’s good hooch?” Clara hissed.

“Oh, relax,” Arabella replied. “Sometimes the clients don’t finish their whole drinks and I take what’s left and pour it in here.”

“What?” Clara spat on the floor. “You gave me backwash?”

“We all put worse things in our mouths all the time. What’s got you so uptight?”

Arabella bent over to slap a mosquito that had landed on her ankle, and Clara noticed the small red bite mark on her skin.

“South Dakota,” Clara said.

Arabella laughed and walked away whistling “Home on the Range.”

Now, as she stretched out on her bed and tried to sleep, Clara could hear all the Avenue noise: car horns, clattering streetcars, riverboats bellowing as they went through the lock and dam. And there was Arabella in the next room, whistling.

When Stasiu arrived to start his shift the next day, Wally was at the counter, chatting with a customer.

“It’s always been bad over there, even before it was the Van Dyke,” Wally said. “It used to be the Nashville, remember? There was a big story back in ‘06. A fella from Saint Paul was wanted for murder. Killed his wife, I think. So he comes across the river and books himself a room at the Nashville, and what does he do? He goes in his room and opens all the gas jets, trying to off himself. The cops nearly kicked the bucket themselves when they went to drag the guy out. I’m tellin’ ya, that building has evil in its mortar joints.”

It seemed like everyone in town wanted to know what was going to happen with Frenchy Ryan’s whorehouse and came to Wally for the lowdown.

Stasiu went into the stock room where the walls muffled the conversation out front. Wally had the day’s orders laid out on slips of paper, and it was Stasiu’s job to get them ready for delivery. He looked through all the slips, but sighed in disappointment when he didn’t see one for 422 Hennepin.

Moments later, Wally shuffled into the stock room and pulled a case of champagne bottles off the shelf.

“Hey, Wally, we’re not taking any orders over to Frenchy today?”

Wally cocked his head to the side. “Don’t you know that all those girls are asleep right now? Frenchy never calls in an order until at least three in the afternoon. Sometimes I don’t hear from her until I’m about ready to close up shop. No, those people are what you call nocturnal. You know, like raccoons and bats. Only come out at night.”

Wally set the champagne on the table and snatched up one of the slips. “You get to go someplace a lot nicer than that grimy old hotel anyway,” Wally said. “There’s a wedding happening at that big house out on Stevens Avenue. You’ll need to make it your first stop.”

Stasiu loaded the morning’s deliveries into the truck and drove out to a gray stone house with tall chimneys that towered over the balustrades on its flat roof, a semi-circular driveway and a wrought iron portico that covered the entryway. Stasiu carried the case of champagne around the side; at houses like this, you never made deliveries at the front. There was always some servant girl waiting to let you in the back gate.

A plain hallway led to a pantry lined with shiny oak glass-fronted cabinets that were full of gleaming china plates. A girl in a starched apron handed him cash after he set the case down. She crossed her arms impatiently as he counted it.

No tip.

Stasiu was annoyed, but he knew better than to say a word about it. He thanked the girl and left to make the rest of his deliveries. As he drove, he remembered his last trip to the Van Dyke, where Frenchy had given them ten dollars. Each.

Clara woke up to the sound of the streetcar clattering down Hennepin Avenue. Hot afternoon light burned through the lace curtains that covered the massive windows. She pushed back the sweaty quilt and slowly sat up. Her head throbbed; she hoped she didn’t have the kind of syphilis that ate away at a person’s brain. Frenchy had a doctor friend who came around sometimes and gave the girls pills if they needed them. The last time he visited, he told Clara that she didn’t have syphilis but that was weeks ago. She could have caught it since then, and now the spirochetes were corkscrewing through her head and wouldn’t stop until she had to leave the brothel for the insane asylum.

She filled the clawfoot tub, hoping the heat would relax the tension in her skull, but the water from the tap was lukewarm. She got in and scrubbed quickly, hopping out before the water got too cold. She wrapped herself in a white silk chiffon trousseau gown. With the shirred elbow-length sleeves and the big bow in front, it would have looked matronly, but for the fact that it was entirely sheer and showed everything.

Clara stepped into a pair of satin slippers and went down to the parlor where Frenchy had breakfast for the girls laid out on an old wooden sideboard. There was no kitchen anywhere in the Van Dyke, except for in the tavern downstairs, but that was separate from the hotel and the owner didn’t like the girls hanging around there. They never got a hot meal unless they went out someplace on their day off. At the Van Dyke, everything came from the icebox. Cold bread, cold meat, cold cheese.

The doorbell sounded and Frenchy went down to answer it. Clara stacked a thick sandwich of ham and havarti and ate it quickly so that the clients wouldn’t see her stuffing her face, but moments later, Frenchy came back up the stairs, alone.

“Just two old biddies from the Women’s Aid Society,” Frenchy grumbled. The WAS were church ladies who thought they could rescue whores by teaching them embroidery. But Clara already knew how to embroider. She’d stitched a vignette onto the back of Samantha’s peignoir using black and gold floss: a busty nun riding a monk’s back. She’d copied it from a dirty European magazine.

An hour before closing, Stasiu sat in the back room, dealing Blackjack for Wally’s friends. The phone jingled, and Wally came back with an order jotted on a scrap of newsprint.

“Frenchy called in her order. Think you can handle this delivery by yourself?” Wally asked, winking.

Stasiu stood on Hennepin Avenue, looking toward the river as he stood in front of the Van Dyke, waiting for someone to answer the bell. The building had two doors: one that led to the ground floor tavern and one that opened to a narrow staircase that led up to Frenchy’s parlor. Storm clouds gathered over the river until the water was the color of slate. A warm, humid breeze stirred the bits of cellophane and torn pieces of newsprint that lined the gutter. Stasiu hoped the rain would hold off until he could get back to Wally’s.

Finally, a face appeared behind the barred glass window and the door opened. Frenchy was dark-haired, with a little bit of gray mixed in, and had greenish-brown eyes with circles underneath. She wore a bright green dress with a belt and brown suede pumps -- fashionable things. It reminded him of the patterns his sister was always trying to copy, only she could never get the stitching right.

“Wally didn’t come?” she asked.

Stasiu shrugged.

“Well, come on up then.” She turned and he followed her up the stairs, gripping the wooden crate full of bourbon and gin as his thighs strained under the load. The parlor was dim, but he recognized her -- the face he’d seen in the window -- stretched out on a settee, wearing a sheer dress that showed everything.

“It looks like you’ve got your first customer, Clara,” said a different girl, who was sitting around in a satin brassiere and girdle. A third girl laughed, and Stasiu recognized her -- she was the fat one who’d had a bite mark on her tit the last time he came through here. She was staring at the bulge under Stasiu’s apron and he turned away, his face flaming. He wished Frenchy would pay him so he could leave, but she was slowly unpacking the crate and setting each bottle out on an old sideboard.

“You all know the rules,” Frenchy said as she opened a billfold and began to count cash. “The boy’s too young. You can’t charge him. Of course…” Frenchy looked up at Stasiu and handed over a stack of cash. “...if you don’t charge him, what do you do with him is nobody’s business.” She grinned, revealing a disorderly row of bottom teeth.

Stasiu stuffed the cash into the pocket on his apron and hurried back down to the delivery truck. He slammed the door shut and turned the engine on but didn’t drive away. Instead, he leaned his forehead against the steering wheel as tears rolled down his face and prayed that his groin would stop aching before he returned to the liquor store.

“You didn’t have to do that, Rosalie,” Clara said as she got up to pour herself a few fingers of the cheap gin that Frenchy bought especially for the girls.

“Do what?” Rosalie asked, making an innocent moue.

“Humiliate the boy.” Clara grimaced as she swallowed the sharp-scented liquor. It was better for bleaching clothes than for drinking but Frenchy wouldn’t let them have anything good.

Rosalie laughed. “Didn’t you see his cock? That apron had a volcano under it.”

Clara rolled her eyes. “He’s a kid. Frenchy said so herself. We can’t even serve him.”

“Frenchy said we can’t take his money,” Rosalie said. “But that don’t mean you can’t take his cherry.”

“There are sows less filthy than you,” Clara retorted. She refilled her glass.

“That’s enough of your bickering,” Frenchy said, sharply. “Will one of you put on some music?”

Arabella got up from the settee and loaded a roll into the dusty player piano that stood in the corner.

At nightfall, Stasiu left the liquor store and waited for the streetcar on Hennepin Avenue. Music and mens’ laughter jangled the windows at the Van Dyke. He glanced up and saw the girl -- Clara -- standing in the third-floor window. She waved at him and smiled wanly. He dashed across the street and leaned on the bell.

He heard Frenchy’s heavy gait on the steps. She crossed her arms and leaned against the open door, grinning.

“You know the deal, junior. I can’t charge you. That means she don’t have to do you if she don’t want to. But you’re welcome to go on up and say hello.”

In the parlor, one of the girls was sitting in a man’s lap with one of her tits hanging out while he tugged on her nipple. In the corridor next to the sideboard full of liquor bottles, a man had a different girl pressed up against the wall, his bare ass showing while he thrust into her.

Stasiu’s heart thundered while he raced up the narrow staircase. The third floor was quiet, save for the moaning that came from one of the rooms; at least up here, the doors were shut. He found the room at the end of the hall -- the one with the windows that faced the street, and knocked softly.

Clara opened the door, the gaslight flickering softly on her face.

“Frenchy said you don’t have to because she can’t charge me.”

Clara smiled, her face amber in the glow of the gas flames. Her fingers softly encircled his wrist as she led him to the bed. As she reached for his belt and pressed her chest gently into his face, the room dissolved into a plane of white.

When it was over, Stasiu let Clara rest her head on his shoulder as his heartbeat slowly returned to normal.

Finally, he asked, “Why’d you do it? Since Frenchy won’t let me pay, I mean?”

She sat up and leaned on her elbow. “Because Frenchy wouldn’t let you pay,” she said, and kissed him.

Statsiu heard a sound that was like an eight-hitch team of horses trampling through the parlor, but then Clara froze and he realized it was footsteps.

“Shit!” she said. “It’s the cops! You better get dressed and get out of here!”

By the time Stasiu was back in his workshirt and pants, the police burst through the door and put them both in handcuffs.

At the police station, Frenchy and Clara told police they’d taken no money from the boy, and they finally let him go, just in time to catch the last streetcar home.

The vice squad padlocked the Van Dyke after the raid. Frenchy dimed on the members of the vice squad who had taken hush money from her and did eight months in the workhouse. Two years later, she became the courtroom sensation of 1940. The judge ordered her to leave Minnesota and to never return. She went to Wisconsin and changed her name.

Clara and Arabella decided they might do better in a town with fewer lawmen, and boarded a train for South Dakota. As the train ripped through the open prairie, Clara began to feel the tight walls of the Van Dyke fall away.

Stasiu didn’t tell Wally and the guys about his night with Clara or getting caught up in the raid. He got a union job making deliveries for the Grain Belt Brewery and eventually married old Mrs. Nowak’s granddaughter, Nadia. Two nights before the wedding, he bedded Nadia in her grandmother’s attic. When she asked if he’d even been with another woman, he said no. He remembered what Mickey had said: The boy can bluff.

Two days later, Nadia floated down the aisle at Holy Cross covered in antique lace and seed pearls. The afternoon sun burned through the stained glass and splashed blue and red and amber all over the front of her white dress.

One night, thirty-three years after the raid on the Van Dyke, Stasiu waited in his car at a stoplight at Hennepin and 5th Street. Flames raged from the third and fourth-floor windows at the old Van Dyke hotel. The red lights of a hook and ladder flashed as a fireman helped an elderly woman out of the same window that Clara had stood in all those years ago. Finally, the firemen trained their hoses on the building and gradually, the orange flames died down.

One of them motioned Stasiu forward, and he drove through the intersection slowly, watching the hot smoke smoldering from the blackened bay windows. A shudder ran down his spine. Then he hit the gas and sped toward the river.

Author’s note: One night, I searched the Star Tribune archives for the term ‘house of ill fame.’ (I was bored.) That’s how I learned about Betty “Frenchy” Ryan, a notorious madam of the gangster era who ran brothels all over town. Her last business address was 422 Hennepin, which is where the Brass Rail bar is now. Though the people of the Minneapolis demimonde believed that Frenchy wouldn’t talk to police, she eventually turned state’s evidence and betrayed the high-ranking members of the vice squad who had taken bribes from her to look the other way on her illicit activities. The Star Tribune devoted several inches of column space to the 1940 trial, and reported breathlessly on Frenchy’s testimony, going so far as to describe the moment when she took off her sunglasses while on the stand. After the trial, she was ordered to leave the state. I couldn’t find any mention of her after that, probably because she changed her name. She was already using several aliases at that point.

I found a Facebook comment from someone who claimed to be a former bartender at the Brass Rail who said that the upper floors of the building were badly fire damaged. A subsequent search of the Star Tribune archives corroborated this statement. There was a bad fire there in 1971, and several residents had to be evacuated. If you go by that address today, you’ll notice that the windows that face the street are blacked out and creepy -- that’s probably because the upper floors of 422 Hennepin have been abandoned since the 1971 fire. They’ve redone the facade, but the glossiness of the blackened windows can’t erase the building’s unsavory past.

Bear in mind I have no first-hand knowledge. I’ve been inside the Brass Rail exactly one time. If you’ve been inside the upper floors of that building, or possess any illuminating knowledge of any kind, dish. Inquiring minds want to know.

I will definitely buy your book of short stories when it is published.